|

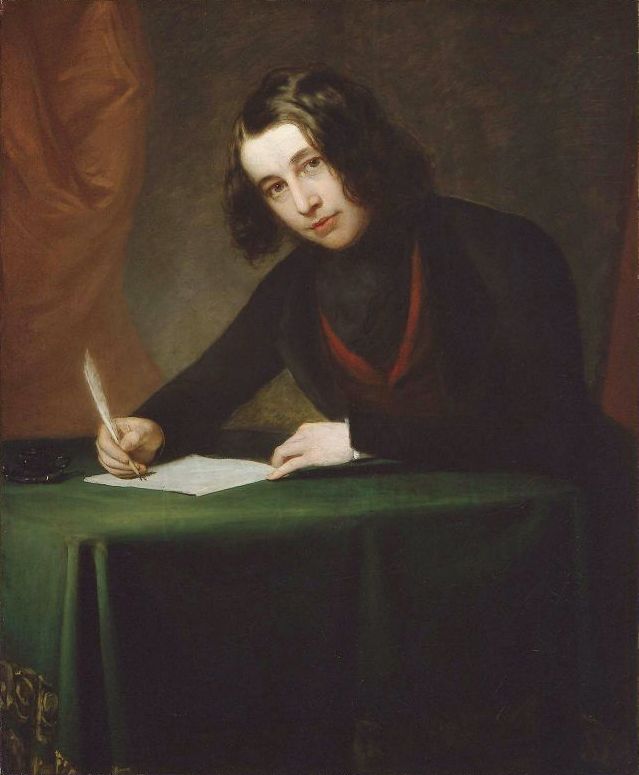

From an oil painting by R. J. Lane, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons Charles Dickens |

Charles Dickens, one of the most celebrated Victorian novelists, immortalized social injustice and the plight of the poor through his literary works.

Among his most widely read novels is Oliver Twist, a powerful narrative that blends realism with sharp satire, unforgettable characters, and a critique of the socioeconomic structure of 19th-century England.

This essay critically analyzes the novel Oliver Twist, focusing on Dickens's writing style, narrative techniques, character creation, use of satire and irony, emotional depth of the characters, depiction of contemporary social issues, and literary influences.

A comprehensive plot summary is also included.

Summary and Plot of Oliver Twist

Published serially between 1837 and 1839, Oliver Twist tells the story of a young orphan, Oliver, born into a workhouse in a nameless English town. The novel opens with a grim tone as Oliver's mother, Agnes Fleming, dies shortly after childbirth, leaving him a nameless child in the uncaring hands of a rigid and cruel system. Dickens establishes early on the systemic negligence of the institutions meant to care for the vulnerable.

Through vivid detail and satirical commentary, he exposes the inhumanity of the workhouse system introduced under the 1834 Poor Law Amendment Act. The workhouse, meant to offer relief to the destitute, becomes a symbol of societal indifference and brutality.

As Oliver grows up, he experiences severe hardship, malnutrition, and abuse at the hands of callous administrators like Mr. Bumble and Mrs. Mann. The infamous scene in which Oliver dares to ask for more gruel—"Please, sir, I want some more"—is not just iconic for its dramatic impact, but also a powerful indictment of a society that criminalizes poverty. His simple request for basic sustenance is met with outrage, and he is swiftly labeled a troublemaker. This moment serves as a turning point, propelling Oliver into a larger, even more dangerous world.

Oliver is subsequently sold to a local undertaker, Mr. Sowerberry, where he is further mistreated and humiliated. Eventually, unable to bear the abuse, he escapes and sets off for London on foot, enduring hunger and exhaustion along the way. His journey to the city symbolizes a plunge from one form of social abandonment into another, as the metropolis is no haven, but rather a place teeming with vice, poverty, and crime.

Upon arrival in London, Oliver is quickly befriended by the Artful Dodger, a street-smart boy who introduces him to Fagin, a sinister old man who runs a gang of child thieves. Fagin, a manipulative and exploitative figure, recruits homeless or orphaned children, training them to become pickpockets for his benefit. The gang includes memorable characters like Charley Bates and the Dodger, who despite their criminal ways, exhibit a boyish charm and camaraderie.

Oliver’s inherent innocence and moral integrity make him ill-suited for a life of crime. During his first outing with the gang, he is wrongly accused of stealing a handkerchief from a well-to-do gentleman, Mr. Brownlow. Fortunately, Mr. Brownlow realizes Oliver’s innocence and takes him into his care. Oliver experiences genuine kindness for the first time, and this period in Mr. Brownlow’s home marks a sharp contrast to the squalor and brutality he has previously known.

Just as Oliver begins to recover and glimpse a better life, he is recaptured by Fagin’s cohort Nancy and the violent criminal Bill Sikes. They fear Oliver might reveal their identities to the authorities. Sikes, a merciless and domineering thief, uses Oliver in a burglary attempt at a countryside estate. However, the plan goes awry when Oliver is shot and abandoned. He is discovered by the residents of the house, Mrs. Maylie and her adopted niece, Rose Maylie, who care for him tenderly. Oliver's stay with the Maylies is a period of healing, moral development, and emotional respite.

As the novel progresses, a parallel plot emerges involving a mysterious man named Monks, who is later revealed to be Oliver's half-brother. Monks conspires with Fagin to destroy Oliver’s future in order to secure the family inheritance for himself. This subplot introduces themes of betrayal, hidden identity, and the corrupting influence of greed. Monks attempts to erase all traces of Oliver’s lineage, including the destruction of a locket and other tokens that could prove his parentage.

Eventually, through a series of revelations and investigative efforts led by Mr. Brownlow, the truth about Oliver's birth and rightful inheritance is uncovered. It is revealed that Oliver is the illegitimate son of Edwin Leeford and Agnes Fleming, and that Monks—born from a different mother—is motivated by resentment and the desire for wealth. The plot threads converge as Fagin is arrested and sentenced to death, while Sikes meets a violent end after murdering Nancy, who had secretly tried to help Oliver escape.

Nancy's murder is one of the most harrowing scenes in the novel. Her character, torn between loyalty to Sikes and her compassion for Oliver, embodies the inner conflict faced by many trapped in cycles of violence and poverty. Her bravery and ultimate sacrifice elevate her to tragic heroine status and underscore Dickens’s broader theme: even in the darkest corners of society, goodness and selflessness can exist.

With the villains defeated and the truth revealed, Oliver is finally adopted by Mr. Brownlow. The novel concludes on a hopeful note, with Oliver surrounded by caring guardians and a secure future. Dickens ensures poetic justice is served: Fagin dies alone in a prison cell, Sikes is consumed by guilt and meets a grisly death, and Monks is exiled and squanders his fortune.

Dickens’s Writing Style in Oliver Twist

|

Francis Alexander, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons Charles Dickens |

He employs third-person omniscient narration, a technique that allows him to delve into the minds and hearts of various characters while also providing commentary that ranges from humorous to scathing.

Often, Dickens steps outside the action to address the reader directly or insert his moral judgments, giving the narrative a dynamic, almost conversational quality.

This intrusive narrative voice is a hallmark of Dickens’s style, allowing him to shape the reader’s ethical understanding and emotional response to the unfolding events.

Dickens’s prose in the novel is vivid and descriptive, often laced with rich imagery and exaggerated expressions designed to stir emotion—be it sympathy, anger, disgust, or amusement. His portrayal of the workhouse is deliberately grim, using bleak and repetitive language to emphasize its oppressive nature. Similarly, the squalid streets and shadowy back alleys of London’s underworld are rendered with almost painterly detail, evoking not only the filth and chaos but also the looming threat of moral and physical decay. These vivid settings form a textured backdrop that reinforces the novel’s central themes.

|

| Charles Dickens Jeremiah Gurney & Sons, 707 Broadway, NY, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons |

His language oscillates between lyrical and coarse, depending on the character or situation. When depicting characters like Oliver, Rose Maylie, or Mr. Brownlow, Dickens employs gentle, elevated diction to reflect their purity and compassion.

In contrast, when narrating scenes involving Fagin, Sikes, or the workhouse officials, his tone becomes cynical, blunt, and often sardonic. This stylistic duality enhances the novel’s moral contrasts and gives the reader clear cues about whom to admire or condemn.

Moreover, Dickens uses melodrama not merely for sensationalism but as a deliberate device to intensify emotional engagement.

Dramatic scenes—such as Nancy’s confrontation with Mr. Brownlow, Sikes’s murder of Nancy, or Oliver’s shooting during the burglary—are laden with heightened emotion, moral conflict, and visual spectacle.

These moments, while sometimes bordering on theatrical excess, are carefully crafted to resonate with Victorian readers accustomed to serialized storytelling and stage drama.

Another notable feature of Dickens’s style in Oliver Twist is his command of serialized narrative techniques. Since the novel was originally published in monthly installments, Dickens structured each chapter to end with suspenseful moments, revelations, or moral dilemmas. This episodic structure not only kept readers eager for the next issue but also contributed to the overall pacing and tension of the story. These serialized elements—cliffhangers, foreshadowing, and subplot layering—are seamlessly integrated into the larger narrative arc.

Dickens also employs recurring motifs and symbolic imagery to reinforce his themes. For example, darkness and shadow often accompany morally corrupt characters or places, while light and open spaces are associated with safety and virtue. These symbolic contrasts deepen the emotional and philosophical undertones of the novel.

In sum, Dickens’s writing style in Oliver Twist is a carefully orchestrated fusion of emotional appeal, social commentary, literary artistry, and theatrical flair. It reflects his commitment to exposing societal injustices while also captivating readers with compelling storytelling. The blend of realism, satire, melodrama, and serialized suspense makes Oliver Twist not just a literary milestone, but a timeless narrative whose style continues to influence writers and resonate with audiences today.

Oliver - Image by ChatGpt

Real-Life Character Creation in Oliver Twist

One of Dickens’s greatest strengths in Oliver Twist is his ability to create vivid, believable characters inspired by real-life figures and societal types. Each character is emblematic of a particular social role or moral condition.

Oliver Twist: The protagonist, Oliver is portrayed with almost saint-like innocence. Despite all the abuse and suffering he endures, Oliver remains uncorrupted—a symbol of innate goodness.

Fagin: A cunning, manipulative figure, Fagin embodies criminal greed and moral decay. His character drew controversy for antisemitic depiction, yet remains one of Dickens’s most psychologically complex villains.

Bill Sikes: A brute driven by violence and fear. Sikes is the embodiment of unchecked aggression, and his eventual downfall is a grim portrayal of poetic justice.

Nancy: A layered character caught between love for Sikes and pity for Oliver. Nancy’s ultimate sacrifice is emotionally powerful and marks her as one of Dickens’s most tragic heroines.

The Artful Dodger: A clever, charismatic boy, representing the youthful victims of urban poverty.

Mr. Brownlow and Rose Maylie: Both function as figures of compassion and moral righteousness.

These characters are not merely fictional; they represent real social dynamics—orphans, criminals, prostitutes, and the bourgeoisie. Dickens’s journalistic eye, sharpened during his early career as a reporter, lends authenticity to his characterizations.

Use of Satire and Irony

Satire and irony are essential elements of Dickens’s narrative technique in Oliver Twist. He mocks the hypocrisy of charitable institutions and the complacency of the upper classes.

The workhouse system is the prime target. The Board of Guardians, including the pompous Mr. Bumble, pretend to help the poor while ensuring they remain miserable. Dickens sarcastically describes how the poor are fed gruel and how asking for more is treated as criminal behavior.

The character of Mr. Bumble, the beadle, is itself a satire of bureaucratic incompetence and moral self-righteousness. His grandiloquent speech, pompous demeanor, and lack of empathy make him a figure of ridicule.

Irony is also used in the narrative tone. For example, Dickens ironically praises the cruelty of institutions under the guise of social benefit. This narrative sarcasm creates a powerful contrast between what is said and what is meant, reinforcing the novel’s moral messages.

Social Conditions Portrayed in the Novel

Oliver Twist is as much a social commentary as it is a literary work. Dickens uses the novel to expose the brutal realities of Victorian England’s underclass. He targets several key social issues:

The Workhouse System: Through Oliver’s early life, Dickens criticizes the inhumane treatment of the poor under the 1834 Poor Law Amendment Act, which forced impoverished people into workhouses.

Child Exploitation: Fagin’s use of children for theft reflects the rampant child labor and criminal exploitation in urban areas.

Urban Crime and Poverty: The squalid streets of London’s East End are vividly depicted as breeding grounds for crime, disease, and despair.

Judicial and Police System: The justice system is portrayed as both incompetent and indifferent. Oliver is nearly imprisoned without evidence, while real criminals like Fagin and Monks operate in the shadows.

Gender Inequality and Prostitution: Nancy’s character sheds light on the limited options available to women, especially those from poor backgrounds.

Emotional Aspects of the Main Characters

|

Jeremiah Gurney & Sons, 707 Broadway, NY, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons Charles Dickens |

Dickens imbues his characters with intense emotional depth. The reader is drawn into Oliver’s fear, innocence, and longing for love. His reactions are often more expressive than verbal, reinforcing his vulnerability.

Nancy’s emotional turmoil is perhaps the most complex. Torn between love for Sikes and guilt over Oliver’s fate, her character wrestles with inner conflict. Her decision to help Oliver at the cost of her life is deeply moving.

Mr. Brownlow’s compassion and Rose’s kindness offer emotional warmth, balancing the novel’s darker elements. Fagin’s fear at the end, as he faces execution, reveals a sudden, harrowing vulnerability. Dickens humanizes even his villains at crucial moments, enhancing emotional resonance.

Influence of Contemporary Writers on Dickens

Dickens was influenced by a range of contemporary and earlier writers:

Henry Fielding and Tobias Smollett: Both authors used the picaresque form, which Dickens adopted in Oliver Twist. The journey of a young protagonist through a corrupt world echoes their novels.

William Hogarth: Though a visual artist, Hogarth’s satirical engravings depicting London’s underbelly influenced Dickens’s depiction of crime and vice.

Thomas Carlyle: His social criticism and concern for the working class shaped Dickens’s own moral and political views.

Elizabeth Gaskell and George Eliot: Though contemporaries, they shared Dickens’s interest in social realism and moral psychology. Gaskell’s Mary Barton and Eliot’s Adam Bede align with the thematic concerns in Oliver Twist.

Gothic and Sentimental Literature: The melodramatic scenes in Oliver Twist, including deathbed scenes and dramatic revelations, are influenced by the Gothic tradition.

Dickens’s originality lies in combining these influences into a unique voice that appeals both to emotion and intellect.

Conclusion

Oliver Twist remains one of the most powerful novels of the 19th century, not only because of its gripping plot and unforgettable characters but also due to its incisive social criticism and emotional force. Charles Dickens masterfully combines literary techniques—satire, irony, vivid description, and emotional pathos—with an enduring moral message. Through Oliver, Nancy, Fagin, and others, Dickens presents a world teetering between corruption and redemption. The novel’s critique of Victorian institutions continues to resonate today, making it a timeless work of literature.

From a literary standpoint, Oliver Twist is a landmark achievement that helped shape the English novel. This in-depth analysis covers topics and aspects like “Dickens’s writing style,” “satire in Oliver Twist,” “realism in Victorian literature,” and “character analysis of Oliver Twist,” ensuring discoverability for readers and students interested in Victorian fiction, literary criticism, and social history.