|

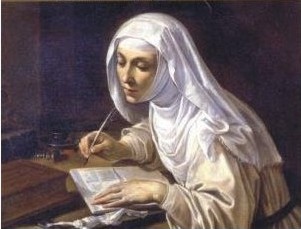

Rutilio di Lorenzo Manetti, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons |

Author: Naval Langa

From my third floor window, the city looked like a woman who had committed suicide, by setting fire to herself. People burnt their own homes, looted their shops, and sent dozens of their own neighbours either in a cemetery or on the pyre. The disturbance had no reason. If it was there; it was utterly baseless. If truth were to be told, it had originated from a minor scuffle.

Where to place an idol of a God:

that was the cause of all the turbulence.

Two different communities claimed ownership of the place, the proposed site for placement of the idol.

There was no possibility of going out of home, as blind curfew was imposed on the roads, on the streets, on every leaf of the trees in the city. So I decided to bury myself in a book. I read literature with the participating passions; sometimes I walked with the characters, too. Though it was difficult to walk along with a man like Jerry Cruncher of A Tale of Two Cities.

Suddenly there was the ringing of the doorbell and thumping of the door. I hurriedly opened to find a woman, frightened and perspiring.

On seeing her, I thought I had never seen her.

‘Ma’am, they have set my house on fire. Some of them wanted to rape me, too. But I… I am here anyhow. Except for you, I don’t know anybody in the city. Would you help me?’

I got her inside. We sat on a sofa, side by side. “Don’t worry, you are safe here,” I assured her about the shelter and my desire. On my insistence, she went for a bath but denied to wear my clothes. After the bath, a cup of warm coffee, and a series of long breaths, she looked to be at ease.

Then I asked her how she knew my address and me.

‘It sounds strange, isn’t it?’

‘No, there is nothing strange in it, Ma’am. I am your creation. You have created me. It’s you who made me educated and incompatible to live with the folk I belong to. Now it’s your duty to settle me in a new life, a better life—you may call it a 'new version’ in your literary terms.’

I could not grasp what she meant by ‘you made me incompatible’.

‘What’s your name?’

‘Farina. You people don’t remember the names of your creations, too.’

Suddenly I recalled I had written a short story before four months or so.

In that story, there was a character. Her name was Farina. She was poor but, she was denying the offer for helping her. She wanted a job, employment of her person, and deployment of her talents. " We aren't beggars" which was what she believed.

Yes, I had caricatured her as A Muslim woman who had studied well, well above the other women in her surround. I had added a pinch of salt of revolt in her.

My sense of perplexity was at the highest. I could not decide how to talk with this fictional woman. I had heard that: ‘artists confront the realities of nature. The artist, a painter, a writer or a poet, deduces the essence of reality. After his or her deduction the artist retells it to others’. But here, the case was reversed. My character had visited my home; a woman from my written pages had jumped out and was sitting before my eyes.

And she believed that I was responsible for her welfare.

It is true that when I ride the horses of imagination, I feel extremely near to the characters. And once a story is finished I sent them, the characters, in oblivion.

**********

AFTER TAKING a not-so-well dinner, we were sitting on the terrace. Not as an obligation, as Farina had pronounced, but as a woman helping another woman, I was mulling over to get her employed somewhere.

‘What type of work you would like to do?’

‘Any work ma’am; I want to live as a free human being, feeling as the soul that has come for some reasons here, here on this earth. You know, now it’s impossible for me to go back to my house. It is burnt, and all the bridges connecting me with my past are blown off.’

After several calculations, I thought about Kanan, the man who knew me since I

was in the city. He could be helpful, I thought.

Though I needed Kanan for certain other purposes, too. I had contemplated at times that for me, in case of my sudden and solitary death, he would be doing things: the things like cremating my body, or putting it on a pyre, or throwing it into a flowing river, or following whatever the procedure available for quick disposal of such stuff –the corpse. I dislike corpses lying in queues.

However, I disliked his ability to sniff things with a dog’s perfection. From a distance of twenty yards, he could smell my presence. He had such a nose. In other assets, he had one ten-by-twenty-sized shop in the middle of the market.

If truth to be told straight away, I liked him; not for his saccharine words or the thick balances he had jailed in his bank accounts, but for he was my friend’s husband. My dead friend’s husband.

*******

WHENEVER I WENT to Kanan’s shop, I hardly could suppress my distaste, his trade-talks and all. I would first puff my distaste and then climb the steps. So I puffed and went through the door.

“Farina, I’ve no idea how to pass my spare time.”

“You’ve no idea how to talk with a woman, too.” I used my unplanned whip and entered. Kanan and Farina instantly turned. Farina gave me a cold drink, a chair, and an affectionate smile. Kanan had cultivated limited chivalry, up to a cold drink and occasional chair. The affection was an additional feature: Farina’s implant.

She was working at Kanan’s shop since the next day she had visited my home. Her house was repaired with help of one NGO I was connected with.

“Farina, where shall we keep these boxes?”

“It will be better if we keep our old stocks on the shelves.”

Kanan spent his time as he spent money. Thriftily. He had used his head in green days of youth, but he could not play it well. Retired hurt. Never tried afterwards to reduce his escalating ignorance.

For passing his spare time he had developed a new sport. Once left alone with empty hours, he would ask for a tea. And as the tea-fumes would rise high, he would mull over increasing his trade, maximising his bank balances.

A woman entered the shop with a load of fat on each of her limbs. Woman customers: Farina’s prerogative.

“Hello ma’am, you were here last week, isn’t it?” She, perhaps, recognised the child from the chocolate he seized, and mom from the brands of hairpins and other accessories.

“Ye…s.” The lady pretended a surprise. The woman, walking on the wrong side of her forties, consumed several seconds in ringing her bangles. “Here is my list and I’m late, too late. Can you help me to pick it up?”

“Ma’am, you feel free. My man will pack all with care, and you’ll get it at your door.”

Kanan had now the luxury of sparing one assistant to run on the roads with bags and boxes on a tricycle-cart. What pleased me were Farina’s accent, the rhythm of words, and the selection of the spaces she put in between. It was evidence of a renewed interest in life.

“Oh. Thanks a lot.”

“Ma’am, we’ve some new jams and pickles. From Amritsar.”

“From Punjab? Let me see.” The lady liked the jam. Added on her list.

*****

THEN FARINA TURNED at me. “You are not coming from the office, isn’t it?”

“No. I’m coming from a garbage

store.” That was how I described my office.

Farina engaged me, and Kanan opted for the boxes. Uneconomical matters hardly inspired him. He had maintained a rigid distance from the matters having no cash value.

He tried to lift a heavy box onto a shelf. The sport was not easy for his short height and cylindrical size. He stood up on a stool of depreciated age and raised the weight.

Once he pulled the box up, he would have realised the mistake. His middle-aged pair of legs with fleshy stock came on the verge of succumbing to the gravitational forces.

He was out to be among imminent damages: injuries to his ankles, one or two ribs were broken, and loss of a full month’s trade. Minimum. But nothing of the sort materialised. The ankles saved, ribs were intact, and trade remained unaffected.

One hand, one helping hand of a woman interfered, and he was rescued.

“Oh, Farina you saved my bones.” He took the support of her shoulder.

The scene, in which Farina helped Kanan, sparked a thought wave in my mind: ‘why this pious lady, Farina, should pass her life alone. And why she could have no future?’ Kanan was used to looking at Farina with a compound of wonder and respect. Standing beside her he seemed to feel like she was standing at a height and he on a narrower strip of land, fenced by four walls of his shop.

Kanan had a permanent digestion problem. When Farina knew about it, she started bringing two lunch boxes: one for her, and one for the ‘greedy trader’. Days flowed out and the catalogue of food in boxes became richer.

Farina’s tightly closed room, which remained locked since her father’s death, was rented for storing Kanan’s new stocks.

‘I had no reason to open that

room when my eyes were dreamless.’ Farina told me once. It meant she had

desisted from believing that nothing could be changed. There had been a

realization of her not-so-depressed face, the realization that she could take

charge of her life-boat.

In a way, she had started to

swim.

ON THE TENTH day, the day on which Kanan, Vijay and I had collective dinner at Farina’s house, I woke up late.

I picked up the newspaper. Coffee cup, still in hand. It was easy to find the headlines of extortions, abductions, or political vomiting on any page of the paper.

But the heading on the last page was appealing.

It reported an appealing subject: one ‘Inter-Religion Marriage.’ In the fine print, the report ran thus:

‘The city hall witnessed a spectacular function last night. People from all sections of society, the traders of the main market and Muslim leaders of our city celebrated the marriage of a grocery trader, Hindu by religion, and a Muslim woman.

Madame City Mayor praised the efforts of all the friends who had made such a reformative event possible. Mr Vijay, Assistant Administrator of the city, thanked all the guests who were present at the function. He described the event as a celebration of matured relationships.

Beside the two-column report, a photograph posed Madame, blessing Farina and Kanan. Vijay stood behind her wearing his administrative suit and a smile of an adopted son on his lips. I made a sign at his photo and dialled the relevant number; perhaps the only relevant number in my life.

“Have you read the Morning News?”

He was on tour. I knew that he would have run-up to the garden, in his jogging suit I had bought on my last outing and would have walked for half an hour. Then he would be sitting stretched on an armchair, with legs on a stool, and sipping before the newspaper.

I heard his sipping, matching with my sipping of the coffee.

‘Yes. You will have to join me as a guarantor of a loan in the city Bank,’ Vijay said.

‘Kanan and Farina have a plan to own a bigger house.’

THE END