|

| Portrait of Charles_Dickens 1872 Daniel Maclise, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons |

In the expansive landscape of Victorian literature, few novels possess the enduring emotional depth, complex character development, and societal critique that mark Charles Dickens’s Great Expectations.

First published in serialized form between 1860 and 1861, this novel encapsulates the rich imagination, moral inquiry, and empathetic storytelling that make Dickens one of the most celebrated novelists in the English language.

Through Great Expectations, Dickens unveils a deeply personal narrative of aspiration, guilt, and redemption, conveyed through his inimitable prose style and a gallery of unforgettable characters.

This essay explores Dickens’s stylistic artistry, his technique of crafting immortal characters, the emotional dimensions of his principal figures, and the literary influences from his contemporaries that helped shape this monumental work.

I. Charles Dickens’s Writing Style: Precision, Pathos, and Parody

Charles Dickens's literary style in Great Expectations exemplifies the hallmarks of his mature phase as a novelist. By this point in his career, Dickens had moved beyond the exuberant and episodic storytelling of his earlier works such as The Pickwick Papers and Oliver Twist, toward a more introspective, symbolic, and structurally refined narrative.

A. The First-Person Narrative

|

| Charles Dickens William Powell Frith, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons Victoria and Albert Musium, London |

Dickens allows the adult Pip to narrate the story of his younger self, creating a layered narrative that juxtaposes innocence and experience.

The dual voice—of the naive boy and the reflective man—adds emotional resonance and a moral undertone to the story.

For example, Pip’s recollections of his shame about Joe’s manners and his misplaced adoration of Estella are tinged with regret and self-awareness.

This duality is further emphasized through Dickens’s linguistic choices. He uses long, winding sentences with rhetorical flourishes when conveying adult Pip’s introspections, while simpler, more concrete language is employed for Pip’s earlier experiences. The contrast underscores Pip’s growth while inviting readers to engage critically with the concept of personal development.

B. Symbolism and Imagery

Charles Dickens's Great Expectations is far more than a simple coming-of-age narrative; it is a psychological and moral odyssey intricately layered with symbolism and vivid imagery. Dickens does not merely tell the story of Pip’s evolution from a humble blacksmith's apprentice to a gentleman plagued by disillusionment; he builds a symbolic architecture that reflects Pip’s inner world and critiques Victorian society’s moral hypocrisies. Through a carefully constructed interplay of recurring images—such as the marshes, Satis House, light and fire—Dickens enriches the narrative with deeper philosophical resonance.

One of the most persistent and haunting images in the novel is the marshes of Kent, the bleak landscape where the story begins and where young Pip first encounters the escaped convict, Abel Magwitch. These desolate, fog-enshrouded marshes operate as a metaphor for Pip’s uncertain moral terrain. They symbolize fear, guilt, and the shadowy regions of conscience.

The very first scene, in which Pip is physically threatened and psychologically unmoored by Magwitch, sets the tone for a recurring theme: the collision between innocence and corruption. The marshes are not just a physical space but a psychological state—a place where the boundaries between good and evil are blurred and where formative trauma is rooted. As Pip progresses on his life’s journey, the memory of the marshes serves as a reminder of his origins, his guilt, and the moral complexity of human identity.

Another powerful symbol in the novel is Satis House, the crumbling mansion where Miss Havisham lives in perpetual mourning. The house is a grand emblem of emotional paralysis and decay. Its very name—“Satis,” implying satisfaction—is ironic, for the house embodies unfulfilled longing, bitterness, and arrested development.

Time has literally stopped in Satis House: clocks are frozen at the hour Miss Havisham received the letter jilting her on her wedding day. Her yellowed bridal gown and cobweb-covered wedding feast become grotesque icons of emotional ruin.

The house becomes a mausoleum of disappointment and vengeance, where Miss Havisham’s despair is preserved like a relic and where Estella is conditioned to wreak emotional havoc on men. The imagery of rot and stagnation that permeates the house is symbolic of the dangers of living in the past and allowing betrayal to curdle into lifelong bitterness.

Throughout the novel, light and fire emerge as central motifs that evolve in meaning depending on context. These elements are not only natural phenomena but also metaphorical devices that Dickens uses to illustrate knowledge, transformation, passion, and even destruction. Early in the novel, candlelight often bathes scenes in a soft, reflective glow, particularly during Pip’s introspective moments.

Light becomes a symbol of awareness, of coming to understand difficult truths about oneself and others. Pip’s encounters with Estella, for instance, are often described in terms of cold, ethereal light—suggesting her beauty and aloofness but also Pip’s idealized, unrealistic perception of her.

Fire, in particular, serves as a double-edged symbol. On one hand, it represents warmth, vitality, and transformation; on the other, it portends danger and annihilation. The most dramatic use of fire in the novel occurs when Miss Havisham is consumed by flames, an event loaded with symbolic meaning.

This sudden blaze, ignited after a rare moment of contrition and emotional vulnerability, becomes a purgative force. Her burning is not just a physical catastrophe but an emblem of emotional catharsis—a violent, painful reckoning for the life she has wasted in resentment and manipulation. In this moment, Dickens seems to suggest that genuine transformation and redemption come only through intense suffering.

Chains and prisons also serve as recurring imagery in Great Expectations, often associated with Magwitch, the convict whose story is central to the moral reversal at the heart of the novel. Magwitch is first seen in leg irons—symbols of criminality and social outcasting—but as Pip learns more about the man, the chains come to represent the unjust limitations placed on people by society.

Magwitch’s generous spirit and sacrifice invert the typical moral expectations of criminality. Pip, once repelled by Magwitch’s physicality and rough manners, comes to admire him. In this way, Dickens uses the imagery of chains to interrogate Victorian assumptions about class, crime, and redemption.

Even weather and landscape serve a symbolic function in the novel. Fog, for instance, is used to denote moral ambiguity and confusion. When Pip is unsure of his path or entangled in self-deception, fog envelops the setting. Conversely, clarity in Pip’s conscience is often accompanied by clear skies or physical openness. Dickens’s symbolic use of the environment mirrors Pip’s inner transformation and serves as an externalization of his psychological state.

In sum, the rich symbolism and carefully curated imagery in Great Expectations are central to its narrative power. Dickens transforms everyday objects and natural phenomena into profound symbols that speak to themes of guilt, ambition, revenge, and redemption. These layers of meaning elevate the novel beyond realism into the realm of allegory, turning Pip’s personal journey into a universal meditation on the human condition.

C. Humor and Irony

|

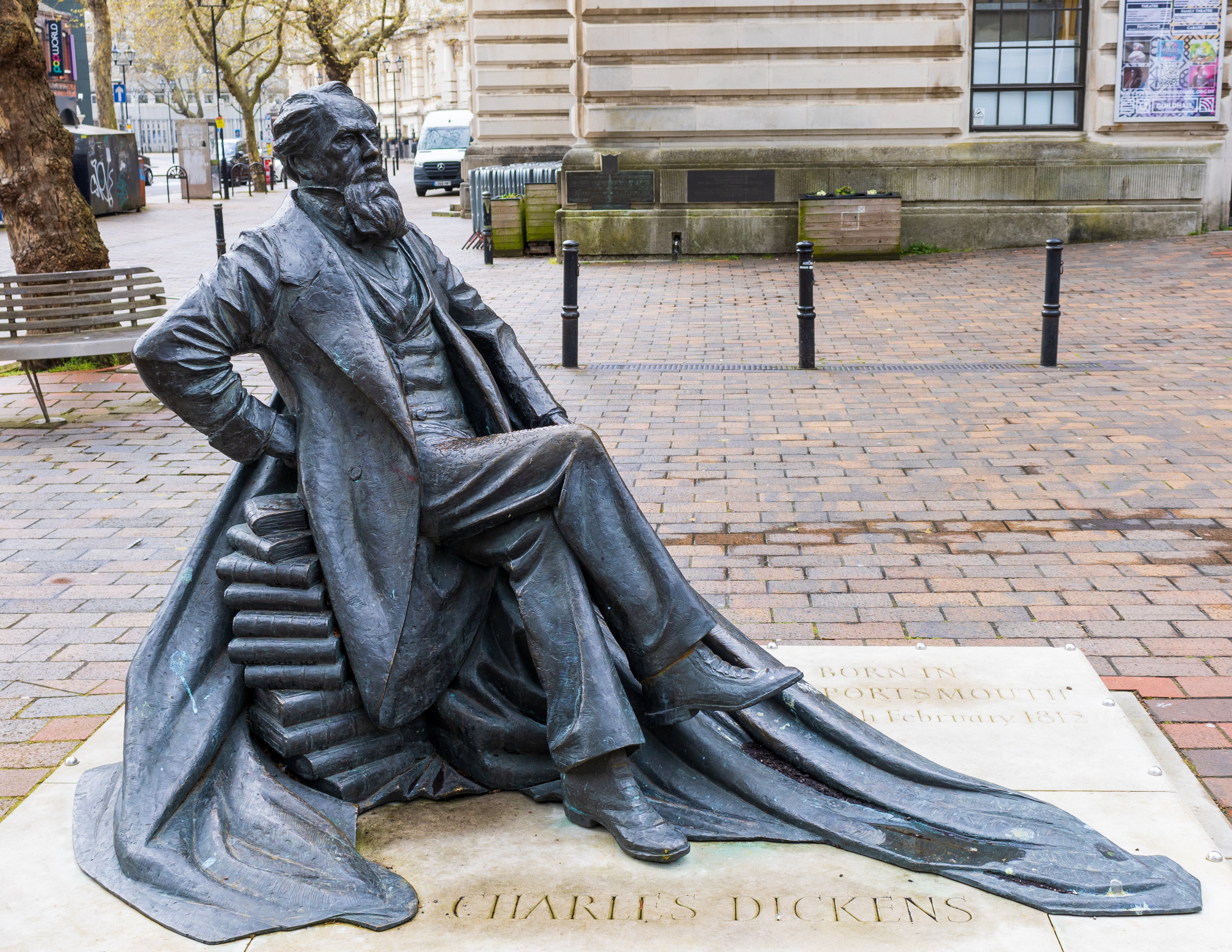

| The wub, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons Charles Dickens statue in Guildhall Square, Portsmouth |

Characters like Mr. Pumblechook, the officious and self-important corn chandler, and the legal eccentric Mr. Jaggers offer comic relief through their mannerisms and exaggerated self-regard.

Dickens uses these characters not only for humor but to critique societal values—such as the hypocrisy of the bourgeoisie and the absurdities of the legal system.

Irony permeates the narrative, particularly in Pip’s misjudgments. His belief that Miss Havisham is his secret benefactor, and that Estella is destined for him, sets the stage for a profound moral lesson about false assumptions and the superficiality of social class.

II. Immortal Characters: Techniques of Psychological and Social Realism

Dickens’s characters in Great Expectations possess a dual identity: they are at once vividly real and allegorically significant. He achieves this through a combination of psychological depth, idiosyncratic detail, and narrative placement within broader social contexts.

A. Pip: The Conflicted Protagonist

|

F.A. Fraser, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons Pip is ashamed of Joe at Satis House, by F. A. Fras |

He evolves from a humble, loving boy into an ambitious and morally conflicted young man. Dickens does not idealize Pip; instead, he exposes his vanity, ingratitude, and self-deception. This complexity makes Pip deeply human and relatable.

What makes Pip immortal in the literary imagination is his capacity for self-reflection.

His emotional journey from shame to remorse, and finally to redemption, mirrors the reader’s own ethical struggles. By placing Pip in morally ambiguous situations—such as his snobbery toward Joe or his internal conflict about accepting Magwitch—Dickens avoids sentimentality and instead presents an honest portrait of human fallibility.

B. Miss Havisham: The Living Ghost

|

| Miss Havisham, Pip, and Estella H. M. Brock, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons |

Miss Havisham, Pip, and Estella, in art from the Imperial Edition of Charles Dickens's Great Expectations. Art by H. M. Brock.

Estella and Pip as part of her revenge against the male gender.

Her character embodies themes of time, decay, and emotional desolation.

Dressed eternally in her wedding gown, surrounded by rotting remnants of her aborted wedding feast, she is both grotesque and pitiable.

Dickens achieves her memorability through dramatic symbolism, psychological fixation, and poetic language.

Her final moment of remorse and tragic death by fire are rendered with operatic intensity, transforming her from a figure of vengeance to one of human vulnerability.

C. Abel Magwitch: The Subverted Criminal

Magwitch makes

himself known

See page for author,

Public domain,

via Wikimedia Commons

himself known

See page for author,

Public domain,

via Wikimedia Commons

Initially introduced as a terrifying escaped convict, Magwitch’s transformation into Pip’s anonymous benefactor is one of Dickens’s greatest narrative feats. Magwitch challenges Victorian prejudices about criminality and social worth.

His unpolished manners contrast sharply with his generous spirit, loyalty, and self-sacrifice.

By revealing Magwitch as Pip’s benefactor, Dickens not only subverts Pip’s assumptions about class and respectability but also elevates Magwitch into a tragic hero.

His rough exterior hides a capacity for love and aspiration that rivals, if not surpasses, that of the genteel classes. Dickens humanizes the criminal class, a recurring theme in his broader social critique.

D. Estella, Joe, Jaggers, and Wemmick

Estella, bred to be cold and heartless, is both a victim and a weapon of Miss Havisham’s emotional manipulations. Her aloofness and cruelty mirror Pip’s internalized class anxieties. Yet she is not entirely unsympathetic—Dickens shows that her emotional limitations are the result of deliberate conditioning, not innate flaw.

Joe Gargery, the blacksmith, embodies humility, moral strength, and unconditional love. In contrast to the more complex characters, Joe’s simplicity is his virtue. He is a touchstone of honesty and decency in Pip’s turbulent world.

Jaggers and Wemmick, Dickens’s portraits of legal professionals, reveal two sides of the Victorian legal system. Jaggers is cold, rational, and professional, while Wemmick exhibits a charming duality—stern at work, affectionate at home. Together, they reflect the contradictions of a society where public and private lives are often disjointed.

III. Emotional Aspects of the Main Characters

One of the novel’s greatest achievements is its emotional depth. Dickens does not merely tell a story; he immerses the reader in the emotional lives of his characters, forging a powerful empathetic bond.

A. Pip’s Emotional Arc

Pip’s inner life is the emotional spine of the novel. His shame over his origins, his yearning for gentility, and his unrequited love for Estella are feelings rendered with aching precision. As he chases his “great expectations,” Pip becomes increasingly alienated from those who love him. His guilt is most painfully felt in his neglect of Joe and Biddy, and in his mistaken assumptions about Miss Havisham and Estella.

Redemption comes only through suffering. Pip’s disillusionment, his nursing of the dying Magwitch, and his humble reconciliation with Joe signal a profound emotional maturation. Dickens uses Pip’s arc to explore themes of repentance, gratitude, and the hollowness of social ambition.

B. Miss Havisham’s Emotional Paralysis

Miss Havisham’s emotional state is one of suspended grief. Her refusal to move on from her jilting has ossified her life. Her interactions with Pip and Estella are attempts to exercise control and exact revenge for a wound that time never healed.

Her eventual breakdown—when she pleads for Pip’s forgiveness—is one of the novel’s most moving moments. It reveals her as a tragic figure, tormented by her own bitterness and the consequences of her manipulation. Her emotional paralysis is both grotesque and heart-wrenching.

C. Magwitch’s Paternal Love

Magwitch’s love for Pip is perhaps the most unexpected and emotionally charged relationship in the novel. It is not romantic or biological, but deeply paternal and sacrificial. His desire to elevate Pip to the status of a gentleman is rooted in gratitude and longing for moral vindication.

The tenderness of Pip’s final vigil at Magwitch’s bedside marks a spiritual reconciliation between the two. Pip’s recognition of Magwitch’s humanity and dignity is a culmination of his emotional evolution.

IV. Dickens and His Contemporaries: Influence and Innovation

Charles Dickens was both a product and a shaper of his literary era. His work reflects a dynamic engagement with the ideas, themes, and stylistic innovations of his contemporaries.

A. Wilkie Collins and the Sensation Novel

Dickens’s close friend and collaborator, Wilkie Collins, was instrumental in popularizing the sensation novel—a genre characterized by mystery, psychological complexity, and dramatic revelation.

Elements of this genre are evident in Great Expectations, particularly in the delayed revelation of Pip’s benefactor and the complex backstory of Estella’s parentage. Dickens absorbed Collins’s narrative suspense and psychological intrigue, integrating them into his own moral framework.

B. Elizabeth Gaskell and Social Realism

Elizabeth Gaskell’s novels, such as Mary Barton and North and South, offered unflinching portrayals of working-class struggles and the impact of industrialization. While Dickens had always addressed social issues, Gaskell’s more overtly realist approach influenced Dickens to deepen his engagement with systemic injustice.

In Great Expectations, Dickens moves beyond caricature to offer nuanced depictions of class, poverty, and the justice system. The transformation of Magwitch from villain to benefactor is emblematic of Dickens’s evolved understanding of social mobility and prejudice.

C. Thomas Carlyle and the Critique of Modernity

Dickens was influenced by the social philosophy of Thomas Carlyle, particularly his critique of materialism and moral decay in the modern age. Pip’s pursuit of wealth and status is ultimately portrayed as spiritually hollow. Like Carlyle, Dickens emphasizes the moral imperative of personal responsibility, authenticity, and human connection.

D. Charles Lamb and the Spirit of Sentiment

The essays of Charles Lamb, with their blend of wit, nostalgia, and personal reflection, influenced Dickens’s tone in Great Expectations. The adult Pip’s rueful, affectionate memories of his youth mirror Lamb’s sentimental approach. Dickens’s use of memory as a tool for moral self-examination owes much to Lamb’s literary style.

V. The Legacy of Great Expectations

According to the Guardian newspaper, this portrait was lost for 174 years, and found in South Africa in 2017. The article says: "It was painted in late 1843 when Dickens, aged 31.

The novel’s characters, particularly Pip, Miss Havisham, and Magwitch, have become archetypes in the literary imagination.

Adapted countless times for stage, film, and television, the story continues to inspire reinterpretation. Its appeal lies not merely in its plot, but in the emotional truth and psychological depth that Dickens brings to every page.

Conclusion

Great Expectations stands as a triumph of literary craft and emotional insight. Through his stylistic virtuosity, Dickens creates a richly layered narrative that combines social critique with deeply personal storytelling. His characters are not only unforgettable but morally and emotionally complex. Pip’s journey from innocence to wisdom, from selfishness to compassion, mirrors our own struggles with identity and conscience.

In crafting this novel, Dickens drew from the talents and insights of his contemporaries, yet ultimately forged a narrative voice entirely his own—one capable of evoking laughter, tears, and self-recognition. More than a tale of a young boy’s ascent and fall, Great Expectations is a profound meditation on what it means to live with integrity in a world shaped by illusion, class, and unfulfilled dreams.

It is this blend of narrative brilliance, emotional authenticity, and moral inquiry that ensures Great Expectations remains, quite justly, one of the greatest novels ever written.