Introduction

|

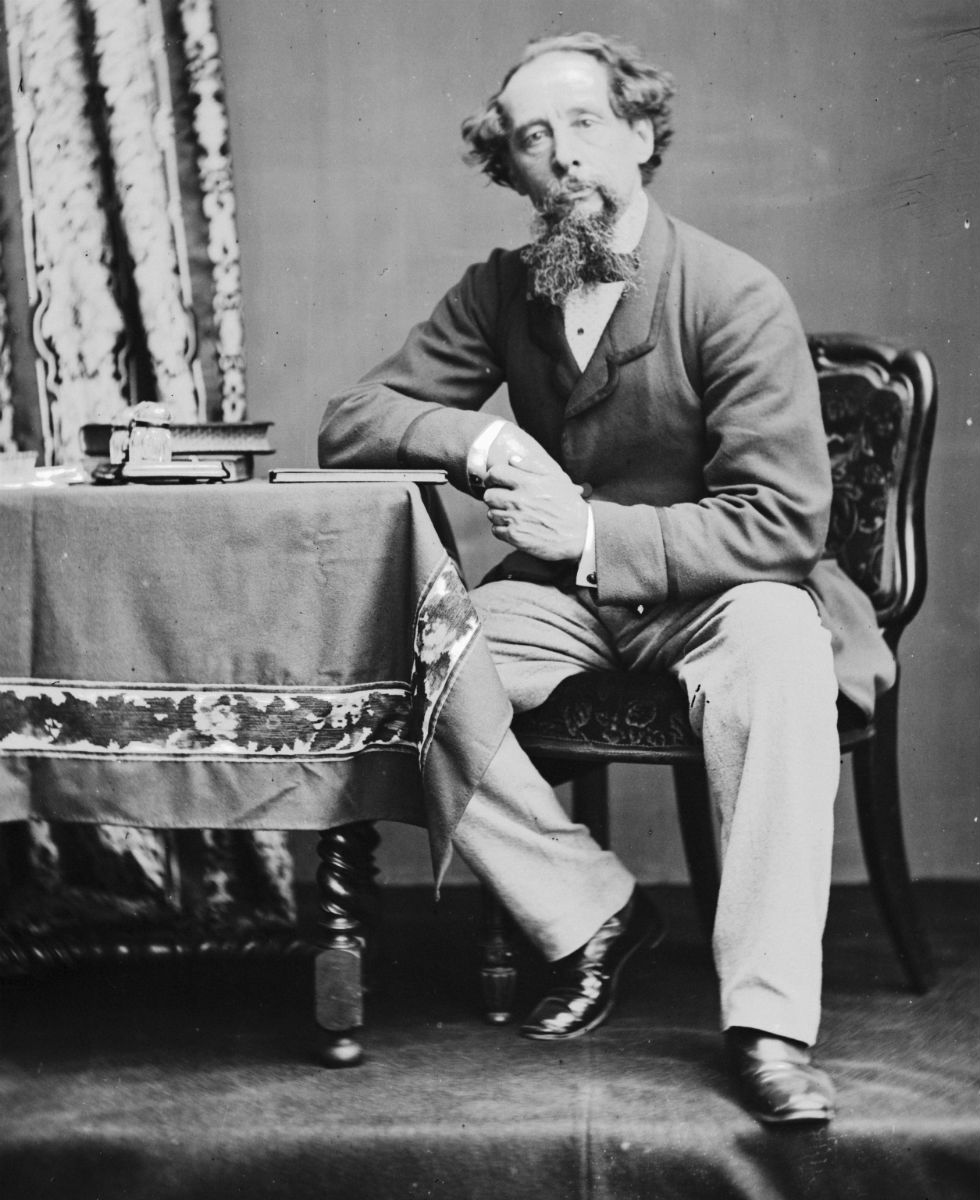

unattributed, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons Charles Dickens |

First published in serial form between 1849 and 1850, this semi-autobiographical narrative remains one of Dickens's most enduring works. Famed for its colorful characters, evocative settings, and moral compass, "David Copperfield" stands as a cornerstone in English literature.

This essay provides a detailed exploration of the novel, offering a summary of the story and its plot, a critical analysis of Dickens’s narrative style, his technique in crafting diverse characters, use of satire and irony, emotional resonance of the main characters, and the influence of contemporary writers on Dickens's creative expression. The following sections aim to offer a deeply analytical perspective on this classic novel.

1. Summary of the Story and Plot

|

| Charles Dickens |

David’s early years are filled with innocence and joy, particularly in the comforting presence of his devoted nurse and family servant, Peggotty.

These years, filled with maternal warmth and simplicity, are presented with nostalgic affection. The bond David forms with Peggotty and her family, including her brother Daniel and his adopted children—Ham and the sweet, tragic Emily—lays a foundational sense of love and belonging that contrasts sharply with the pain that follows.

This idyllic beginning is disrupted when Clara remarries Edward Murdstone, a cold, authoritarian man who disapproves of David’s sensitivity and imagination. Murdstone’s cruel nature becomes evident when he brings his equally harsh sister, Miss Jane Murdstone, to the household. David's spirit is broken by their emotional and physical abuse, culminating in a traumatic episode where he bites Mr. Murdstone and is immediately sent away to Salem House, a boarding school run by the tyrannical Mr. Creakle.

At Salem House, David befriends the charming but unreliable James Steerforth and the sincere and good-natured Tommy Traddles. These relationships are significant, marking David’s early exposure to the complexities of friendship and the moral ambiguities in people’s characters.

Tragedy strikes when David’s mother and infant brother die during his school term. This leaves David utterly abandoned. .jpg)

Charles Dickens's David Copperfield

Harold Copping, Public domain,

via Wikimedia Commons

Without his mother’s protection, he is sent to work at Murdstone and Grinby’s wine bottling factory in London. This period is perhaps the bleakest in the novel and is drawn directly from Dickens’s own traumatic experiences working in a blacking factory as a child.

The grim working conditions and emotional isolation highlight the harsh realities of child labor in 19th-century England.

Through David’s eyes, Dickens delivers a searing critique of a society that allows its most vulnerable to suffer in silence.

Feeling utterly alone, David undertakes a remarkable journey on foot to Dover to seek refuge with his eccentric great-aunt, Betsey Trotwood. This journey is symbolic not only of physical endurance but also emotional rebirth. Aunt Betsey, though initially stern and unconventional, surprises David by taking him in and offering him unconditional support. She becomes one of the most nurturing figures in his life. With her guidance, David receives a stable home, proper education, and the opportunity to shape his future. Her insistence on calling him "Trotwood" signals his symbolic rebirth and new beginning.

As David matures, he navigates the complexities of adulthood while pursuing a professional career. He initially trains to become a proctor (a type of lawyer) and later follows his passion to become a writer. Along the way, Dickens introduces a vivid and diverse array of characters that reflect the breadth of Victorian society. One of the most memorable is the ever-hopeful Mr. Micawber, who, despite chronic financial instability, remains buoyantly optimistic and eloquent. Micawber’s enduring refrain, "Something will turn up," encapsulates the resilient human spirit. His character is said to be based on Dickens’s own father, John Dickens, whose financial irresponsibility deeply affected the author’s youth.

Equally significant is Uriah Heep, the novel’s primary antagonist. He is obsequious, manipulative, and deceitful, always insisting on his own “humbleness” as he schemes to exploit others for personal gain. Uriah’s gradual rise and eventual exposure are handled with psychological depth, making him one of Dickens’s most unforgettable villains. His interactions with David, Agnes, and Mr. Wickfield highlight the corrosive effects of hypocrisy and unchecked ambition.

David’s personal life takes a poignant turn when he falls in love with and marries the charming but childlike Dora Spenlow. While their early courtship is romantic and light-hearted, their marriage is marked by emotional frustration. Dora, though loving, is ill-suited for the practical demands of married life. Her early death, while tragic, acts as a catalyst for David’s emotional growth and introspection. He comes to understand the difference between idealized love and enduring companionship. Through this emotional journey, Dickens explores themes of maturity, emotional resilience, and the often-painful process of self-discovery.

Throughout the novel, the character of Agnes Wickfield remains a quiet, moral center. Her steadfast support and unspoken love for David contrast sharply with the fleeting passions and illusions he experiences with Dora. Agnes embodies the Victorian ideal of womanhood: intelligent, compassionate, and self-sacrificing. When David eventually realizes his deep emotional bond with Agnes, it feels both inevitable and satisfying. Their union symbolizes emotional fulfillment, mutual respect, and enduring love.

As David’s fortunes stabilize, many of the novel’s threads come together. The Micawbers expose Uriah Heep’s financial misdeeds, restoring honor to the Wickfield household. Steerforth, whose charm masked a lack of integrity, meets a tragic end after seducing and abandoning Emily. Ham dies trying to save a shipwrecked sailor—ironically, Steerforth—highlighting themes of sacrifice and redemption. Traddles becomes a successful and contented man, proving that integrity and perseverance yield quiet triumphs.

By the novel’s end, David is a successful author, married to Agnes, and surrounded by friends who have endured life’s many hardships with grace and resilience. His journey from a vulnerable orphan to a mature, self-aware adult mirrors Dickens’s own life trajectory. David Copperfield is thus not only a richly textured bildungsroman but also a veiled autobiography, reflecting the author’s enduring preoccupations with poverty, injustice, love, and redemption.

The story wooven in David Copperfield offers a more layered exploration of the characters, relationships, and emotional arcs that define the novel. Dickens’s genius lies in weaving personal tragedy with societal critique, creating a story that resonates across time and generations. His detailed characterizations, moral complexities, and emotional insight continue to captivate readers, making David Copperfield one of the most beloved novels in English literature.

2. Dickens’s Narrative Style

|

unattributed, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons Charles Dickens |

This autobiographical form is crucial in establishing an emotional connection between the protagonist and the reader. From the very beginning, David becomes not just a character but a voice recounting his life with vulnerability and insight.

The first-person narration allows readers to witness David's emotional and intellectual development as he reflects on past experiences with the wisdom of hindsight.

This narrative strategy gives the novel its autobiographical quality, reinforcing the Bildungsroman structure and enabling Dickens to chronicle the protagonist's journey from childhood innocence to mature self-awareness.

One of the most remarkable aspects of Dickens’s technique is how he uses language to enhance narrative depth. His prose in David Copperfield is rich and evocative, marked by poetic flourishes that illuminate the inner lives of characters and the symbolic significance of events. Dickens frequently uses metaphors, similes, and personification to transform mundane settings into charged landscapes. For example, the sea is a powerful and recurrent motif throughout the novel. It is emblematic of fate, mystery, and moral consequence.

The coastal town of Yarmouth, with its unpredictable waves and chilling winds, mirrors David’s own internal turmoil. The sea ultimately becomes the agent of poetic justice, claiming the life of James Steerforth during a tempestuous storm—a moment that signifies both retribution and the moral order that Dickens subtly weaves into his narrative.

The use of symbolic imagery is not confined to the sea alone. Houses and rooms often reflect the emotional atmosphere of their inhabitants. Blunderstone Rookery, David's childhood home, transforms from a warm haven into a place of fear and repression after the arrival of Mr. Murdstone. Similarly, the Micawbers' perpetually chaotic household is emblematic of Mr. Micawber’s flamboyant optimism and financial irresponsibility. Dickens’s settings are never static; they function almost as characters in their own right, evolving in response to the protagonist’s growth and changing emotional states.

Another significant feature of Dickens’s narrative style in David Copperfield is the episodic structure that reflects its original serial publication. Serialization had a profound influence on Dickens's pacing and chapter construction. Each installment was carefully crafted to end on a note of emotional or narrative tension—often with a cliffhanger or unresolved conflict—to ensure continued reader engagement.

This approach not only sustained the interest of Victorian audiences but also contributed to the novel's unique rhythm and expansive scope. The story unfolds in a series of vividly drawn episodes, each contributing to David’s maturation and the novel’s broader themes of social injustice, resilience, and redemption.

Despite its episodic nature, David Copperfield achieves remarkable cohesion, primarily through Dickens’s careful use of recurring characters, motifs, and themes. Characters such as Mr. Micawber, Uriah Heep, Agnes Wickfield, and Steerforth recur at crucial points in the narrative, each representing different moral paths and emotional lessons for David. These characters are not merely static representations but evolve along with the protagonist, often revealing new facets upon each reappearance. Dickens’s genius lies in his ability to interweave these characters into the overarching narrative, ensuring that their individual arcs serve the larger moral and thematic framework of the novel.

Furthermore, Dickens demonstrates mastery in manipulating time within the first-person framework. He often foreshadows future events or reflects back on earlier ones, creating a layered narrative that mimics the workings of memory itself. This interplay between past and present deepens the reader’s understanding of David’s emotional and psychological development. For instance, David’s retrospective realization of Agnes's quiet strength and devotion adds poignancy to earlier scenes where her significance had not yet been fully grasped.

Dickens’s voice as the narrator also changes subtly as the story progresses. Early chapters, told from a child's perspective, are imbued with innocence and wonder, whereas later sections take on a more reflective and analytical tone. This modulation of narrative voice mirrors David’s growth and contributes to the authenticity of his character. The shifts in tone—from humorous to tragic, from naive to introspective—enhance the emotional resonance of the novel.

Finally, Dickens’s narrative technique includes an acute awareness of social realities. Through David’s eyes, the reader experiences the harshness of child labor, the rigidity of class structures, and the vulnerability of women and children in Victorian society. Dickens doesn’t merely describe these conditions—he evokes them through the lived experiences of his characters, lending urgency and emotional weight to the story. His narrative thus becomes a vehicle not only for personal development but also for social commentary.

In conclusion, the narrative style of David Copperfield showcases Charles Dickens’s literary craftsmanship at its finest. By employing a first-person autobiographical structure, poetic language, symbolic imagery, and episodic storytelling, Dickens creates a deeply immersive and emotionally complex narrative. These elements combine to make David Copperfield not just a chronicle of one man’s life, but a richly textured reflection of human experience, memory, and moral growth.

3. Technique of Creating Diverse Characters

One of Dickens’s most celebrated talents is his ability to create a wide array of unforgettable characters. In "David Copperfield," he populates the narrative with personalities that are distinct, multidimensional, and symbolic of broader societal archetypes.

David Copperfield himself is the lens through which we view Victorian England. His journey from victim to self-possessed individual parallels Dickens’s own rise from hardship to literary fame.

Agnes Wickfield, with her serenity and moral fortitude, serves as the novel’s moral compass. She is the embodiment of Victorian feminine virtue: patient, pure, and devoted.

Dora Spenlow represents romantic idealism. Though beautiful and charming, she is emotionally and intellectually immature. Her early death symbolizes the end of David’s naive notions of love.

Mr. Micawber is Dickens’s comic masterpiece. Bombastic, verbose, and always on the verge of financial ruin, he is nonetheless a figure of integrity and loyalty.

Uriah Heep, the sycophantic clerk, embodies hypocrisy and the corrosive effects of social resentment. His affected humility—"I am a very 'umble person"—masks ruthless ambition.

Steerforth, the privileged aristocrat, is handsome and charismatic but morally vacuous. His betrayal of Little Em’ly and eventual demise offer a critique of unchecked privilege.

Each character is given a unique voice, appearance, and moral dimension. Dickens often uses suggestive naming to reflect personality traits—Heep is creepy and serpentine; Micawber sounds jovial and unreliable. These stylistic choices help anchor the reader’s emotional response and deepen engagement.

4. Use of Satire and Irony

|

John & Charles Watkins, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons Charles Dickens |

Education: The sadistic Mr. Creakle’s school, which punishes more than it teaches, mocks the Victorian model of rote learning and corporal punishment. Dickens ridicules a system that values obedience over intellect.

Law and Bureaucracy: Dickens often satirizes the legal profession. The firm of Spenlow and Jorkins is portrayed as archaic and ineffectual. The idea that Jorkins is a distant and severe authority figure—while actually being weak and malleable—exposes the absurdities of hierarchical workplace dynamics.

Class Pretension: Through characters like Steerforth and Mrs. Steerforth, Dickens criticizes the moral emptiness of the upper class. They are given every advantage but use their privilege for self-indulgence rather than good.

Irony often appears in how characters perceive themselves versus how they are perceived by others. Uriah Heep sees himself as humble and wronged, while readers recognize his manipulation. Mr. Micawber’s financial incompetence is ironically matched by his confidence in his economic philosophy.

5. Emotional Aspects of Main Characters

The emotional development of characters in "David Copperfield" provides the novel’s deepest resonance.

David Copperfield: He begins as an emotionally vulnerable child, shaped by trauma and abandonment. Over time, his experiences—grief, unrequited love, betrayal—lead him to emotional maturity. His relationship with Agnes marks the culmination of this development.

Agnes Wickfield: Her quiet strength and moral clarity form the emotional bedrock of the novel. Though she suffers silently, her unwavering support shapes David’s moral compass.

Dora Spenlow: Dora’s inability to adapt to the responsibilities of marriage is both tragic and poignant. Her decline and eventual death force David to re-evaluate his understanding of love and partnership.

Mr. Micawber: His emotional highs and lows mirror the economic volatility of lower-middle-class life. Despite frequent despair, he remains fundamentally hopeful, embodying Dickens’s belief in the redemptive power of optimism.

Betsey Trotwood: Initially eccentric and brusque, she evolves into one of David’s most loving guardians. Her emotional transformation underscores the novel’s theme of unexpected kindness.

These emotional arcs enrich the novel, allowing readers to see characters grow, falter, and redeem themselves.

6. Influence of Contemporary Writers

Charles Dickens was not writing in a vacuum. He was deeply influenced by and responded to the literary movements of his time.

William Makepeace Thackeray: As a fellow novelist of manners and satire, Thackeray’s "Vanity Fair" explores themes of social climbing and moral ambiguity. While Dickens is more sentimental, both authors examine the pitfalls of Victorian society.

Elizabeth Gaskell: Her social realism and attention to class issues complement Dickens’s thematic concerns. Gaskell’s "Mary Barton" and "North and South" examine industrial England with the same urgency Dickens brings to London’s underclass.

Thomas Carlyle: His essays on labor, industrialism, and moral responsibility find echoes in Dickens’s attention to working-class struggles and critiques of utilitarianism.

The Brontë Sisters: Charlotte Brontë’s introspective characterizations, particularly in "Jane Eyre," influenced Dickens’s portrayal of psychological depth and emotional realism.

Dickens synthesized these influences into a unique style marked by humor, sentimentality, and a fierce commitment to social justice.

7. Legacy and Enduring Relevance

"David Copperfield" remains one of the most beloved novels in English literature. Its themes—resilience in the face of adversity, the corrupting influence of power, the value of kindness—are timeless. Its characters are archetypes that continue to influence literature, film, and popular culture.

Pupularity-wise, it ranks highly in searches related to "classic English novels," "Charles Dickens character analysis," "Victorian literature," and "bildungsroman examples."

Modern readers find relevance in David’s quest for identity and self-worth. The novel’s treatment of trauma, emotional intelligence, and social mobility aligns with contemporary concerns, proving that great literature transcends its era.

Conclusion

Charles Dickens’s "David Copperfield" is a masterwork of literary art and social commentary. Through its intricate plot, diverse characters, biting satire, and emotional depth, it captures the essence of the human experience. Dickens’s writing style, marked by vivid description and narrative ingenuity, ensures that readers are emotionally and intellectually engaged.

Influenced by his literary contemporaries and shaped by personal hardships, Dickens created a novel that continues to inspire, educate, and resonate. Whether analyzed for academic study, literary enrichment, "David Copperfield" remains a shining example of 19th-century English literature at its most powerful and poignant.

The Pencil portrait of Charles Dickens is generated by using AI Tools, thus it has no copy right.