Introduction

|

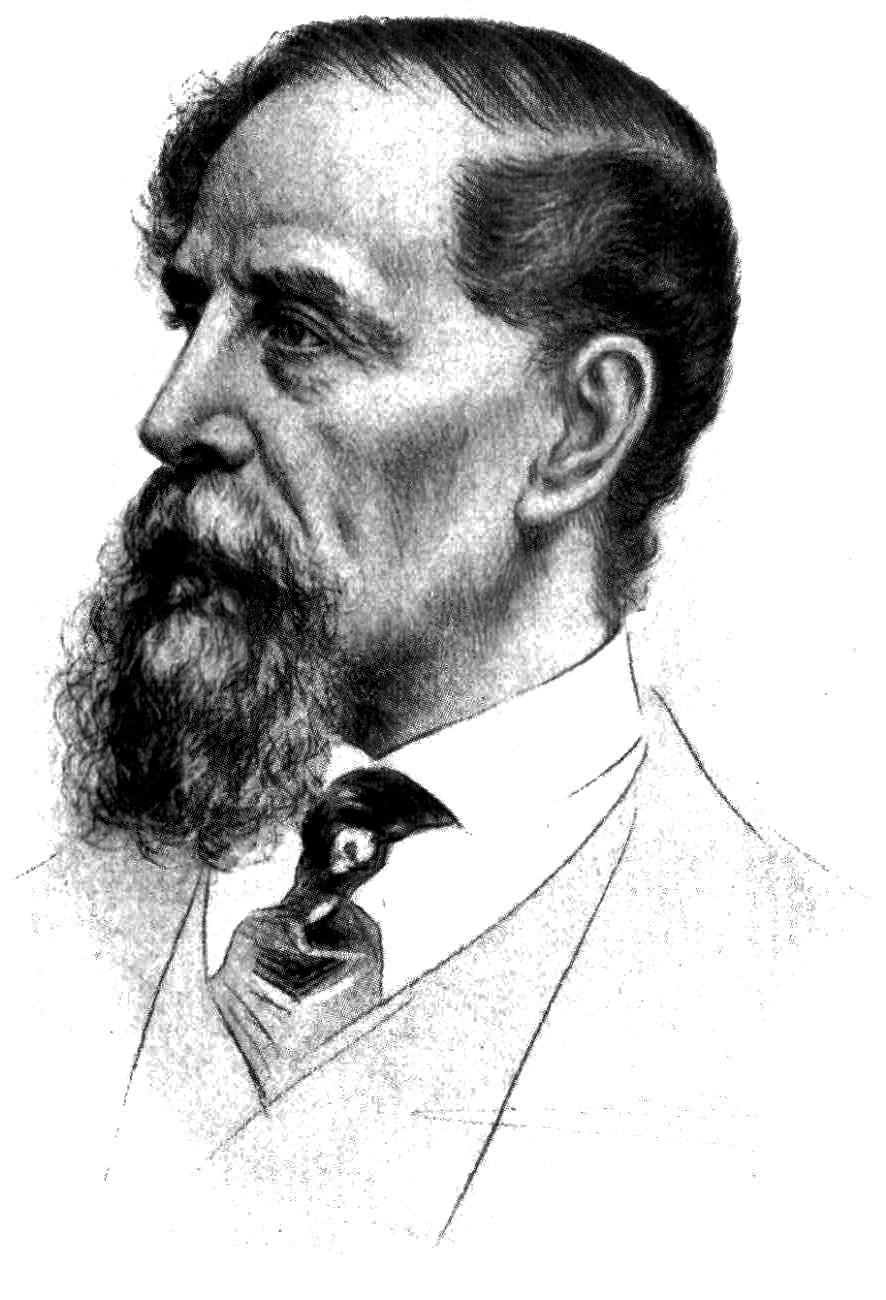

J. Gurney & Son, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons Charles Dickens |

Combining elements of satire, detective fiction, courtroom drama, and romance, Dickens constructs a powerful critique of 19th-century British society, particularly targeting the legal system.

With dual narrative voices and an expansive cast of characters, Bleak House explores the emotional, social, and moral consequences of institutional negligence and personal greed.

This essay critically examines Dickens’ distinctive style of writing, his techniques for creating immortal characters, the use of satire and irony, emotional depth of the main characters, the influence of his contemporaries, and includes a comprehensive summary of the plot.

Summary of the Story and Plot of Bleak House

The novel opens with a striking description of thick, all-consuming fog that engulfs London—a vivid metaphor for the impenetrable and bewildering workings of the Court of Chancery. This dense atmosphere sets the tone for a story built around the fictional lawsuit Jarndyce and Jarndyce, a legal quagmire over a disputed will that has ensnared generations in hopeless litigation, draining them of both fortune and spirit.

At the center of the story is Esther Summerson, introduced as a modest and thoughtful orphan raised under the harsh supervision of her godmother. Upon her godmother’s death, Esther is welcomed into the household of the kindly and principled John Jarndyce, who resides at Bleak House. There, she becomes a close companion to Ada Clare and Richard Carstone—two young cousins who are among the potential inheritors of the Jarndyce estate.

Despite John Jarndyce’s warnings about the ruinous nature of the legal case, Richard becomes increasingly obsessed with its potential outcome. His faith in the court system, however, proves to be tragically misplaced. As the case drags on without resolution, Richard’s health, fortune, and hopes deteriorate. Ada, ever devoted, stays by his side, though ultimately powerless to alter his fate.

Running parallel to Esther’s journey is the compelling narrative of Lady Dedlock, a beautiful and emotionally restrained noblewoman married to the elderly Sir Leicester Dedlock. Beneath her composed exterior lies a long-buried secret—she is Esther’s biological mother, having borne her out of wedlock in her youth. As this secret edges closer to exposure, Lady Dedlock’s carefully constructed world begins to collapse.

The unravelling of Lady Dedlock’s past is driven by Mr. Bucket, a diligent and sharp-witted detective who represents one of the earliest examples of a professional investigator in English literature. His methodical pursuit of truth brings many secrets to light, including the identity of a murderer and the real circumstances surrounding Esther’s birth.

Overwhelmed by shame and fear of disgrace, Lady Dedlock ultimately flees and dies in solitude. Esther, upon discovering the truth about her origins, experiences a profound internal transformation. She matures emotionally and gains the confidence to pursue love and happiness. Her quiet resilience culminates in a fulfilling union with Dr. Allan Woodcourt, a noble and compassionate physician who has long admired her.

As the various storylines converge, the Jarndyce and Jarndyce case is abruptly dismissed when the estate is entirely consumed by legal costs, rendering the entire effort moot. In a final act of generosity, John Jarndyce steps aside from his own romantic feelings for Esther, blessing her marriage to Dr. Woodcourt and gifting them a new home—another Bleak House, symbolizing a fresh start free of the shadows of the past.

Dickens’ Style of Writing in Bleak House

|

enwiki, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons |

One of the most remarkable aspects of this novel is its dual narrative framework, which alternates between the third-person omniscient perspective and the deeply personal first-person voice of Esther Summerson.

This stylistic innovation allows Dickens to provide a sweeping societal critique while also delving into the emotional and moral intricacies of individual experience.

Esther’s narrative is tender, introspective, and grounded in ethical sensitivity. Through her voice, Dickens constructs a character that is not only central to the emotional core of the novel but also serves as a moral lens through which the story is filtered. Her humility, compassion, and sense of duty guide readers through the moral landscape of the plot.

In contrast, the omniscient narrative is detached, ironic, and often scathing in its depiction of societal decay, particularly in its portrayal of institutions like the Court of Chancery. This narrator sees all, critiques all, and spares no sentiment in exposing the systemic dysfunctions and hypocrisies of Victorian England.

Dickens' prose is layered and rich, often poetic in its rhythm and vocabulary. The novel’s famous opening passage, which describes the heavy, clinging fog engulfing London, stands as one of the most powerful symbolic openings in literature. The fog does not merely describe the physical environment; it also metaphorically represents the moral and procedural obscurity of the legal system that permeates the novel.

Dickens uses this imagery to create a visual and atmospheric motif that recurs throughout the book, enveloping characters, settings, and events in a sense of moral uncertainty.

What makes Dickens’ style particularly effective in Bleak House is his ability to balance this rich, symbolic language with moments of sharp, journalistic clarity. He frequently shifts from ornate, almost baroque descriptions to concise, action-driven scenes that keep the reader engaged.

This stylistic range allows him to move fluidly between the novel’s many plot threads and emotional tones, from the tragic to the comedic, from the grotesque to the sublime.

Dickens also relies heavily on literary devices such as repetition, contrast, and irony to deepen thematic resonance. Repetition emphasizes the cyclical nature of institutional failure, while contrasts—between characters, settings, or moral outlooks—highlight the disparities that define Victorian society. Irony is a constant presence in Bleak House, employed to expose the contradictions and delusions of the characters and institutions.

Another hallmark of Dickens’ style in this novel is his masterful use of serialization. Writing for a periodical audience, Dickens structured the novel to maintain suspense and reader engagement across numerous installments. Each chapter is crafted to stand alone in terms of entertainment and emotional impact, while also contributing to the broader narrative tapestry.

He plants narrative seeds early in the story that come to fruition hundreds of pages later, creating a rich network of interwoven subplots and character arcs.

The novel’s language also reveals Dickens’ sharp ear for dialogue and regional dialects. Characters are distinguished by the way they speak, and their voices often carry layers of class, profession, and personal history. This attentiveness to spoken language adds realism and immediacy to his characters, making even the most minor figures memorable and authentic.

Overall, Dickens’ stylistic choices in Bleak House serve not merely to embellish the text, but to unify its diverse elements—emotional, moral, and social—into a coherent and impactful whole. Through innovative structure, evocative imagery, and rhetorical precision, Dickens delivers a novel that is both a narrative masterpiece and a compelling critique of the society in which he lived.

Technique of Creating Immortal Characters

Dickens’ characters in Bleak House are memorable not only because of their vivid names and physical descriptions but also due to the moral or social truths they embody. Each character represents a specific societal issue or personal flaw, yet Dickens breathes life into them with psychological nuance.

Esther Summerson, for instance, may seem self-effacing and demure, but her quiet strength and compassion make her one of Dickens’ most admirable heroines. John Jarndyce is a study in benevolence, embodying the ideal of moral conscience. Richard Carstone is a tragic figure, illustrating the corrosive effects of misplaced hope and obsession.

The grotesque characters, such as the parasitic Mr. Vholes and the hypocritical Mrs. Jellyby, are sketched with satirical precision. Yet, even minor characters—like the ragged boy Jo, who utters the unforgettable line "I don't know nothink"—evoke deep empathy and remain etched in literary memory.

Mr. Tulkinghorn, the sinister lawyer, and Mr. Bucket, the meticulous detective, are early prototypes of noir archetypes in modern detective fiction. Lady Dedlock’s tragic depth and hidden past elevate her to the level of a Greek heroine, shrouded in dignity and despair.

Satire and Irony in Bleak House

|

| Charles Dickens, 1868 From a photograph by Gurney, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons |

Characters like Mrs. Jellyby, obsessed with distant philanthropy while neglecting her own children, satirize Victorian society’s moral posturing.

The character of Harold Skimpole, who disguises selfishness as childlike innocence, is another satirical gem—based, controversially, on Dickens’ friend Leigh Hunt.

Irony permeates the narrative structure. The contrast between appearances and reality, public virtue and private vice, is starkly portrayed. Sir Leicester Dedlock’s rigid aristocratic pride is ironically juxtaposed with his genuine love for his wife.

Even the character of Mr. Guppy, the bumbling yet ambitious law clerk, becomes a vehicle for Dickens to mock social climbing and false propriety. Dickens’ satire in Bleak House is not merely humorous but morally charged, urging readers to reflect on injustice and hypocrisy.

Emotional Aspects of the Main Characters

The emotional resonance of Bleak House is one of its greatest strengths. Esther’s journey from an insecure orphan to a woman who asserts her identity is deeply moving. Her discovery of her parentage, her struggle with feelings of unworthiness, and her quiet endurance make her emotionally compelling.

Lady Dedlock’s story, though tragic, is filled with emotional complexity. Her remorse, secrecy, and eventual self-sacrifice underscore the limitations placed on women and the burdens of class and reputation.

Richard Carstone’s decline from a hopeful young man to a disillusioned, sickly victim of the legal system is portrayed with poignancy. Ada’s steadfast loyalty, though passive, adds a layer of emotional constancy.

Jo, the street-sweeper boy, evokes universal compassion. His death is one of the most heart-wrenching moments in Dickens’ oeuvre. Even minor characters, like the servant Charley and the brickmaker’s wife Jenny, add emotional texture to the narrative.

The novel also captures communal emotion—compassion, grief, rage, and disillusionment—that rises from social injustice. Dickens doesn't just narrate these emotions; he makes readers feel them.

Influences from Contemporary Writers

While Dickens was an innovator, he was also in dialogue with his literary contemporaries. He shared narrative concerns with authors like William Makepeace Thackeray, whose novel Vanity Fair offered similarly scathing social commentary. The narrative complexity and moral ambiguity in Bleak House resonate with the works of George Eliot, who admired Dickens’ characterization but favored psychological depth.

Dickens also drew from the gothic tradition, borrowing atmospheric tension and family secrets reminiscent of Ann Radcliffe and Mary Shelley. His portrayal of the legal system echoes the scathing critiques found in the writings of Bentham and Carlyle.

Wilkie Collins, Dickens' close friend and later collaborator on The Woman in White, likely influenced the detective elements of Bleak House, particularly in the creation of Mr. Bucket. Dickens' awareness of serialized novel techniques and theatrical pacing also reflects his professional background as a journalist and stage performer.

Conclusion

Bleak House stands as a towering achievement in Victorian literature, blending social criticism with emotional richness and narrative innovation. Through dual narration, a sprawling yet coherent plot, and masterful character creation, Dickens illuminates the human consequences of systemic failure.

His writing style—rich in metaphor, irony, and satire—draws readers into a world that is both vividly imagined and deeply reflective of real social ills. Characters like Esther, Lady Dedlock, and Jo transcend the page, becoming emblematic of human endurance, regret, and innocence.

Influenced by his contemporaries yet uniquely his own, Dickens’ vision in Bleak House is both a mirror and a moral compass. It remains relevant not just for its literary artistry but for its urgent call for compassion, reform, and justice.