|

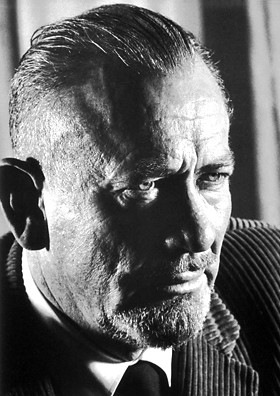

| John Steinbeck Nobel Foundation, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons {{PD-US}} |

“The Human Journey in John Steinbeck’s The Grapes of Wrath”

[Opening – Setting the Tone]

Steinbeck’s The Grapes of Wrath, published in 1939, stands among the greatest novels of the twentieth century—not only for its artistry but for its moral courage. It speaks to us even now, in our own century of uncertainty, reminding us that the bonds between human beings are the last defense against despair.

I. The Soil of the Story

Let us begin where all great epics begin—with the land.

The novel opens amid the vast Oklahoma plains, in the heart of the Dust Bowl. The Joad family, humble tenant farmers, live off this stubborn soil until nature turns against them. Years of drought and reckless farming practices have transformed once-fertile fields into dust. The wind blows the topsoil away, leaving only hunger and ruin behind. Steinbeck writes in the opening chapter:

“And then the dispossessed were drawn west—from Kansas, Oklahoma, Texas, New Mexico, from Nevada and Arkansas, families, tribes, dusted out, tractored out, car-loads, caravans, homeless and hungry; twenty thousand and fifty thousand and a hundred thousand and two hundred thousand.”

“The bank is something more than men, I tell you. It’s the monster. Men made it, but they can’t control it.”

Thus begins the Joad family’s odyssey—Tom Joad, freshly released from prison for killing a man in self-defense; Ma and Pa Joad, weary yet unbroken; Grandpa, stubborn and earthy; Grandma, fierce in her faith; Uncle John, haunted by guilt; and the younger children, Rosasharn—Rose of Sharon—pregnant with hope, and the rest, innocent and bewildered.

They pile their lives into a rickety Hudson truck and head west along Route 66—the “Mother Road”—lured by handbills promising work in California, that fabled Eden of fruit and promise.

II. The Road West: A Modern Exodus

Steinbeck punctuates the Joads’ journey with short, lyrical interchapters—vignettes that broaden the scope of the novel. In these sections, the story of one family becomes the story of hundreds of thousands. We hear the voices of the anonymous: the shopkeeper, the mechanic, the land agent, the waitress, the migrant child. These collective voices form a kind of modern chorus, echoing across the land.

In one of these interchapters, Steinbeck describes the migration in a passage that could apply to any displaced people, in any age:

“And because they were in flight and frightened because they had lost land, they were fierce and they were cunning. And because they had nothing left but themselves, they began to build up a new life—a life based on the thing they could not lose: their pride, their faith, and their community.”

This is the moral heartbeat of The Grapes of Wrath: when all material things are taken, what remains is the unbreakable thread of human solidarity.

III. The Losses Along the Way

The Joads learn that California, far from a paradise, is a land of exploitation. The fields are owned by vast agribusinesses that keep wages low by importing desperate workers from the east. Those who came dreaming of abundance find themselves starving amid the orchards.

At one heartbreaking moment, Steinbeck shows oranges being drenched with kerosene so they cannot be eaten by the poor:

“And in the eyes of the hungry there is a growing wrath. In the souls of the people the grapes of wrath are filling and growing heavy, growing heavy for the vintage.”

This passage gives the novel its title. It is a biblical image—drawn from the Book of Revelation—but Steinbeck transforms it into a moral prophecy. When injustice becomes too great, when hunger and humiliation ripen past endurance, the wrath of the oppressed will burst forth. Not in violence alone, but in the awakening of human conscience.

IV. The People’s Prophet: Jim Casy

Among the Joads travels a former preacher, Jim Casy—a character who becomes the novel’s spiritual center. Once a man of the cloth, Casy has lost his conventional faith but found a deeper one in humanity itself. Early in the story, he tells Tom Joad:

“I ain’t preachin’ no more much. The sperit’s strong in the people itself—all of ’em.”

Casy’s philosophy is simple yet revolutionary: holiness resides not in the church or in the individual soul, but in the collective spirit of mankind. He says:

“Maybe all men got one big soul ever’body’s a part of.”

This idea—that salvation lies in shared struggle—becomes the moral seed that blossoms in Tom Joad later in the novel.

Casy’s eventual death is both martyrdom and rebirth. He is struck down while organizing workers for fair wages, echoing Christ’s sacrifice. And in that moment, the torch passes to Tom.

V. Tom Joad’s Awakening

Tom’s transformation from self-concerned ex-convict to social prophet marks one of the great character evolutions in modern fiction. When he kills a man who murdered Jim Casy, he becomes an outlaw once again, but this time his cause is righteous. He goes into hiding, and before he leaves, he speaks to his mother in words that have echoed across generations of readers and social movements alike:

“I’ll be ever’where—wherever you look. Wherever they’s a fight so hungry people can eat, I’ll be there. Wherever they’s a cop beatin’ up a guy, I’ll be there. If Casy knowed, why, I’ll be in the way guys yell when they’re mad—and I’ll be in the way kids laugh when they’re hungry and they know supper’s ready.”

These words are not only Tom’s farewell to his mother—they are Steinbeck’s benediction to humanity. In them, the private becomes universal. The individual struggle merges with the collective will to justice.

VI. Ma Joad: The Eternal Mother

“We’re the people that live. They ain’t gonna wipe us out. Why, we’re the people—we go on.”

Ma Joad’s quiet strength carries the family when all else fails. In her, Steinbeck embodies the archetype of the universal mother—compassionate, indomitable, unyielding in hope. She represents not only the endurance of women but the endurance of humanity itself.

VII. Rose of Sharon and the Final Scene

Steinbeck writes:

“Her hand moved behind his head and supported it. Her fingers moved gently in his hair. She looked up and across the barn, and her lips came together in a silent cry.”

This final act of selfless compassion transcends tragedy. In that gesture, the novel completes its circle—from isolation to community, from loss to giving, from death to the renewal of life. The milk of human kindness flows even in desolation.

It is not an ending of despair, but of grace.

VIII. The Novel’s Structure and Symbolism

Steinbeck’s structure alternates between the intimate story of the Joads and the broader, panoramic interchapters. This dual rhythm mirrors the pulse of life itself—the individual and the collective, the personal and the social.

The prose, often biblical in cadence, transforms the mundane into the mythic. The road west becomes a pilgrimage. The family becomes the nation. The dust, the drought, the journey, the harvest—all are symbols of the human condition.

“He is trampling out the vintage where the grapes of wrath are stored.”

Steinbeck borrows that imagery to suggest that divine justice ripens slowly, but inevitably. The suffering of the poor, once fermented, will yield not only anger but awakening.

IX. Why The Grapes of Wrath Still Matters

Now, more than eight decades after its publication, The Grapes of Wrath remains startlingly relevant. In a world where millions are still displaced by war, climate change, and economic upheaval, Steinbeck’s migrants are our contemporaries. The Joads walk beside today’s refugees, the unemployed, the homeless, the indebted. Their story is the story of every generation that has ever asked: How do we live with dignity when the world takes everything away?

The novel challenges us to see beyond ourselves. It teaches that moral progress begins when we feel another’s pain as our own. Steinbeck once said his purpose was “to rip a reader’s nerves out by the roots.” But he did more than that—he gave us the courage to hope.

In an age of division, The Grapes of Wrath offers a radical antidote: empathy. It insists that our survival as a people depends not on competition, but on compassion. It shows that the measure of a civilization is not its wealth, but its mercy.

X. Critical Reception and Legacy

The novel’s influence extended far beyond literature. It inspired reform in labor laws, influenced social movements, and became a moral touchstone for the American conscience. In 1962, Steinbeck was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature, and the Swedish Academy cited his “sympathetic humor and keen social perception.”

Even today, lines from The Grapes of Wrath echo in political speeches, protest songs, and public debates. The 1940 film adaptation by John Ford, starring Henry Fonda as Tom Joad, carried the story to millions and immortalized the character’s famous farewell speech.

But perhaps Steinbeck’s greatest legacy is emotional rather than political. He gave voice to the voiceless. He taught readers not just to see suffering, but to feel it—and, feeling it, to act.

XI. A Book to Be Read and Remembered

To read The Grapes of Wrath is to be humbled and uplifted at once—to weep for what people suffer, and to marvel at what they survive. It teaches that even in the darkest times, the human spirit, like the earth after rain, can still bloom again.

As Steinbeck himself wrote in a later essay:

“In every bit of honest writing in the world, there is a base theme. Try to understand men, if you understand each other you will be kind to each other.”

That is the gospel according to The Grapes of Wrath.

XII. Conclusion: The Living Flame

When you next open its pages, hear again the rumble of the migrant trucks, see the dust rising like smoke, feel the hunger that drives the Joads forward. But above all, feel the unbroken pulse of humanity that beats beneath the hardship.

For in every act of kindness, every cry for justice, every gesture of shared bread, Tom Joad still walks among us. Ma Joad still endures. Rose of Sharon still offers her compassion. And the grapes of wrath—those bitter fruits of suffering—are still ripening, waiting for us to harvest not vengeance, but wisdom.

Thank you.