Ladies and gentlemen, honored listeners,

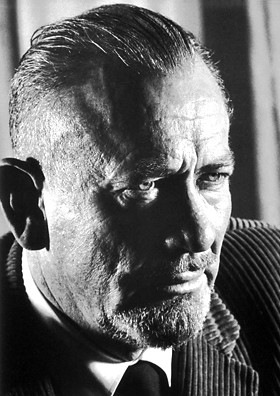

John Steinbeck

Nobel Foundation, Public domain,

via Wikimedia Commons

This evening, I invite you to walk with me through the dust and over the broken highways of America during one of its harshest chapters, the Great Depression.

We walk not as casual observers but with the intimate guidance of John Steinbeck’s The Grapes of Wrath, a novel of such scope and humanity that it does not merely recount a story but engraves itself upon the moral conscience of those who read it.

My purpose tonight is to recount for you the arc of this novel—its summary and plot—and then to show you why Steinbeck’s creation is not only literature of the highest order but a living, breathing testimony of resilience, suffering, and justice.

The Setting: Dust and Dispossession

The Grapes of Wrath, first published in 1939, is deeply rooted in history. It emerges from the Great Depression, when economic collapse coincided with ecological devastation in the Dust Bowl states, particularly Oklahoma. Families who had farmed the land for generations suddenly found themselves stripped of their homes by drought, dust storms, and foreclosure by distant banks. They became, as Steinbeck writes, “the dispossessed.”

One of the novel’s earliest and most haunting scenes shows a turtle struggling to cross a road, inching its way forward, buffeted by obstacles, yet persisting. That turtle is more than a reptile—it is the symbol of every human soul in this novel, struggling across the barren terrain of existence.

|

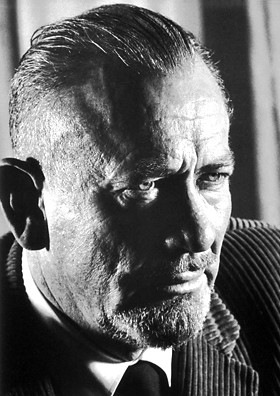

| John Steinbeck Nobel Foundation, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons |

The Joad Family: A Portrait of Struggle

At the heart of Steinbeck’s novel stands the Joad family. They are not rich, they are not powerful—they are ordinary tenant farmers. Tom Joad, recently released from prison on parole, is the figure through whom we first enter the story.

He returns to find his family farm abandoned, repossessed by the banks. His parents, Ma and Pa Joad, his siblings, and his grandparents are preparing to leave, for there is nothing left for them in Oklahoma.

They have heard whispers of a promised land: California. Pamphlets and rumors speak of fertile orchards and endless jobs. To desperate families, California gleams like Eden. And so, they pack what little remains of their lives into a battered truck and set out west along Route 66, that legendary highway of migration.

This exodus is not theirs alone. Along the road, they join countless other families, all driven by the same desperation. Steinbeck describes this migration in sweeping terms, entire caravans of the poor moving westward like a tide.

The Journey: Loss and Harsh Realities

The journey is no idyll. The Joads suffer losses almost immediately. The grandparents, too frail for the ordeal, die along the way. Money dwindles. Food is scarce. The California they imagined as paradise increasingly reveals itself as a mirage.

Upon arrival, they discover a land not of promise but of exploitation. Migrant camps overflow with starving families. Wages are pitiful, deliberately suppressed by growers who manipulate the surplus of desperate laborers. Signs read: “No Help Wanted.” Police harass the migrants, whom they derisively call “Okies.”

Yet amid degradation, Steinbeck shows the flowering of human dignity. In the government-run Weedpatch Camp, the Joads find a rare glimpse of decency, order, and self-respect. There is no charity there, only mutual support. Neighbors help one another because they must. Steinbeck reminds us: though institutions may fail, human solidarity remains.

Tom Joad’s Awakening

The novel’s trajectory is not only the Joads’ struggle for survival but also Tom Joad’s moral awakening. Guided by the former preacher Jim Casy, Tom learns to see beyond personal survival to collective responsibility. Casy himself is a Christ-like figure, a man who once preached formal religion but now seeks holiness in human connection and shared suffering. He tells Tom: “Maybe all men got one big soul ever’body’s a part of.”

Casey’s activism leads to his death at the hands of strikebreakers, but his spirit carries on in Tom. When Tom, too, must flee after retaliating against those who killed Casy, he leaves his mother with words that echo across literature:

“I’ll be ever’where—wherever you look. Wherever they’s a fight so hungry people can eat, I’ll be there. Wherever they’s a cop beatin’ up a guy, I’ll be there. Wherever they’s somebody fightin’ for their rights, I’ll be there.”

This moment transforms Tom from an ex-convict concerned only with his family to a prophet of justice, a voice for the oppressed.

|

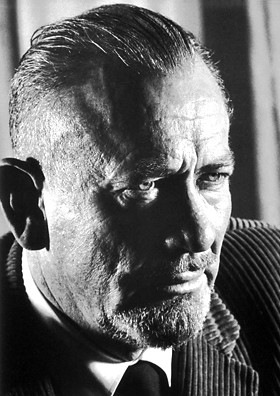

| John Steinbeck Nobel Foundation, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons |

The Climactic Act of Compassion

The novel closes with one of the most shocking and tender acts of human compassion in literature.

After the Joads take shelter in a barn during a flood, they encounter a starving man who cannot eat solid food.

Rose of Sharon, Tom’s sister, who has just lost her baby, nurses the dying man with her own breast milk. Steinbeck leaves the scene wordless, except for the image of her faint smile.

It is an image of despair transformed into sustenance, of suffering turned into life-giving generosity. In that moment, Steinbeck affirms the possibility of human kindness in the bleakest circumstances.

|

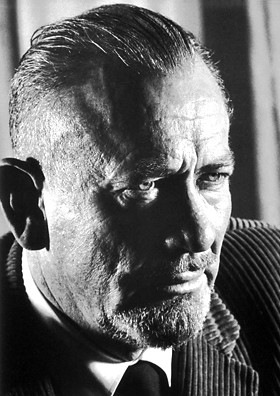

| John Steinbeck Nobel Foundation, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons |

Why The Grapes of Wrath Is Special

Now, why does this novel stand apart? Why must we read it, why must we tell it again and again? I offer several reasons.

1. Historical Witness

The novel is a record of a real American tragedy—the dispossession of farmers, the cruelty of unregulated capitalism, the suffering of migrants. It preserves in literature what might otherwise have been forgotten. It allows us to hear the voices of those whose suffering was voiceless.

2. The Power of Realism and Poetry

Steinbeck did not merely write a social tract; he created art. His prose is at once stark and lyrical. He alternates between intimate family scenes and sweeping intercalary chapters that give the panorama of the entire migration. Through this structure, he weaves the personal into the universal.

3. Moral Vision

The novel compels us to confront moral questions: What is justice? Who bears responsibility for the poor? Are we merely individuals, or are we bound together in a shared human destiny?

4. Resonance Across Time

Though rooted in the 1930s, its themes echo into the present: economic inequality, displacement, the plight of migrants, the dignity of labor. In every age of crisis, Steinbeck’s novel speaks anew.

The Enduring Spirit of Ma Joad

Perhaps the strongest symbol of resilience is Ma Joad. She is the backbone of the family, the one who holds them together when Pa falters. She declares: “We’re the people that live. They ain’t gonna wipe us out. Why, we’re the people—we go on.”

Her voice is not loud or political, but it is unbreakable. In Ma Joad, Steinbeck gives us the embodiment of endurance.

The Grapes of Wrath as a Call to Conscience

Ladies and gentlemen, when Steinbeck wrote this novel, he faced bitter criticism. The book was burned, banned, denounced as un-American. Why? Because it told truths uncomfortable to the powerful. But time has vindicated it. Today, it is celebrated not as propaganda but as one of the greatest American novels ever written.

And what does it call us to do? It calls us to compassion. It calls us to justice. It calls us to remember that literature is not only to entertain but to awaken. It asks us to see in the Joads our own brothers and sisters, to hear in Tom Joad’s words an unfinished task: to stand wherever people are hungry, wherever people are beaten down, wherever dignity is denied.

Conclusion

To read The Grapes of Wrath is to journey with the Joad family across dust, hunger, loss, and hope. It is to witness despair but also to glimpse the stubborn light of human solidarity. It is a book that does not let us remain spectators; it presses us to ask: What kind of society do we build? Whom do we leave behind?

John Steinbeck has given us not only a novel but a mirror and a challenge. If we allow it, the story of the Joads will not end in 1939—it will live within us, urging us toward a world where no one is dispossessed, where justice flows like water, and where, in Steinbeck’s words, “the people go on.”

Thank you.