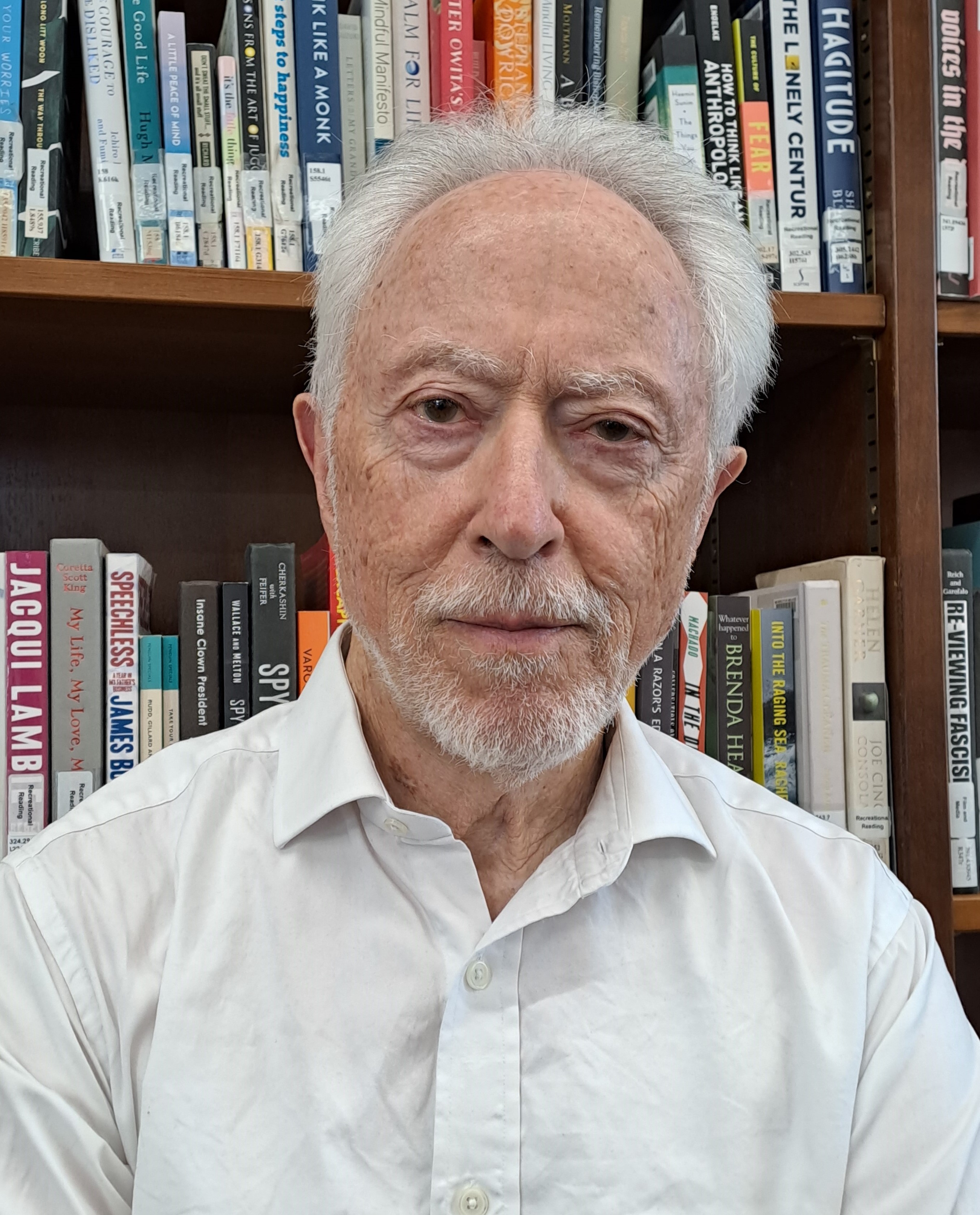

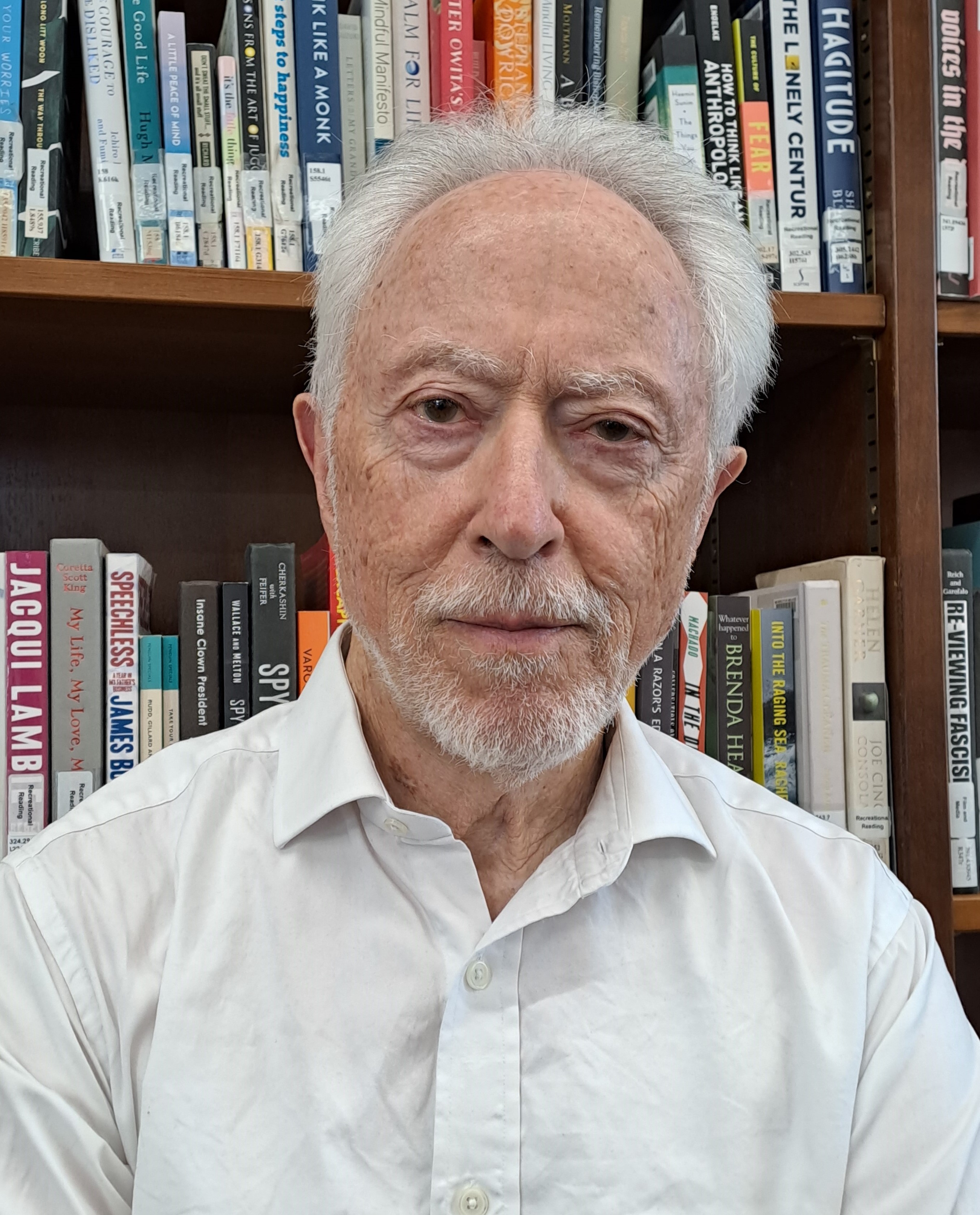

Laterthanyouthink, CC BY-SA 4.0,

via Wikimedia Commons

J. M. Coetzee

via Wikimedia Commons

J. M. Coetzee

INTRODUCTION

J. M. Coetzee’s In the Heart of the Country, first published in 1977, is a masterful exploration of isolation, power, and obsession set in the South African hinterlands.

The novel centers on Magda, a woman living alone on her father’s farm, and unfolds as a series of confessional monologues that blend reality, memory, and fantasy.

Coetzee’s sparse, precise prose conveys the starkness of the landscape and the psychological intensity of Magda’s inner life. This comprehensive summary will provide a scene-by-scene breakdown, thematic exploration, and integration of quotes to illuminate the novel’s complex narrative.

SHORT SUMMARY

J. M. Coetzee’s 1977 novel, In the Heart of the Country, is a powerful and unsettling work of postmodern and postcolonial fiction. Set in the desolate Karoo region of South Africa, the novel offers a fragmented and deeply psychological narrative told through the eyes of its sole protagonist, Magda. This novel is not driven by a conventional plot but by the descent of its character into isolation and madness, making it a pivotal text in Coetzee’s acclaimed body of work.

The story is presented as a series of diary-like entries, each numbered and often contradictory, blurring the line between reality and Magda’s rich inner world. The plot is initially defined by a single, shocking event: Magda's claim that she has murdered her patriarchal father. The opening lines, “I have killed him. I have killed my father,” set a tone of violence and irreversible action. However, the novel immediately introduces narrative uncertainty, as the father reappears, his existence and death becoming fluid and unreliable parts of Magda’s deteriorating reality.

Magda’s life on the remote farm is one of profound loneliness and intellectual frustration. She is alienated from her father, a symbol of the oppressive colonial patriarchy, and yearns for connection and meaning. Her days are filled with fantasies of escape and violence, and her entries reflect a complex obsession with language itself as a tool of both power and subjugation.

The arrival of a mixed-race servant, Hendrik, and his son, Klein-Hendrik, introduces a new dynamic. The men become objects of Magda’s fantasies, as she projects her desires and anxieties onto them. She imagines a new life with them, a life of love and family, which stands in stark contrast to her desolate reality.

The narrative’s core is the exploration of Magda’s inner world, where violence, desire, and colonialism are inextricably linked. The farm becomes a microcosm of South African society, with its rigid racial and power hierarchies. As the novel progresses, the distinction between what is real and what is imagined collapses entirely. Magda’s communication breaks down, and she resorts to writing on stones, a futile attempt to leave a message in a world that has ceased to make sense.

Foe | ||

Ultimately, In the Heart of the Country is a profound meditation on themes of alienation, the legacy of colonialism, and the crisis of language. The novel’s ambiguous ending leaves Magda in a state of isolated stasis, her narrative unraveling along with her sanity. It stands as a chilling and unforgettable portrait of a mind in crisis and a society on the verge of its own profound change.

ANALYTICAL SUMMARY

Chronological Scene-by-Scene Breakdown

1. Introduction to Magda and the Farm

The novel opens with Magda recounting the deserted, sprawling farm in the Karoo region. The farm is depicted as an almost timeless space, reflecting Magda’s isolation. Her narrative immediately establishes her obsessive preoccupation with her father: “I have been alone here since my mother died. Alone with my father.” The opening situates the reader in Magda’s psychological world, where loneliness amplifies her fixation on power, control, and narrative authority.

Magda’s reflections set the tone for the novel’s central motifs: isolation, dominance, and the collapse of familial and social structures. The harsh South African landscape mirrors the emotional barrenness of Magda’s existence.

2. Magda’s Relationship with Her Father

Magda’s father is a figure of authority, distant yet central to her imagination. Scenes depicting their interactions reveal a mix of fear, desire, and resentment. Magda frequently oscillates between admiration and hostility toward him, suggesting deep psychological conflict. She imagines scenarios in which she exerts control over him, writing, “I will kill him, or he will kill me. It is a question of who will dominate.”

These passages highlight the novel’s engagement with power dynamics within the family. Coetzee’s depiction of Magda’s obsession is unsettling but insightful, illustrating the destructive potential of isolation and unresolved familial tensions.

3. Daily Life and Monotony on the Farm

Much of the narrative focuses on Magda’s routine chores, emphasizing the monotony and physical demands of farm life. Scenes describing her labor, such as tending animals or managing the land, are interspersed with introspective passages. These moments blur the line between reality and fantasy, as Magda projects emotional and moral significance onto mundane acts. For example, she writes, “I walk the land as if to measure my life against it, to see if there is room for me, or if I have already been swallowed.”

Here, Coetzee explores themes of human isolation in a vast, indifferent landscape and the existential struggle to assert meaning in a seemingly meaningless world.

4. Imagined Scenarios of Violence and Control

As the narrative progresses, Magda increasingly indulges in violent fantasies involving her father and other potential figures of intrusion. She imagines poisoning her father, imagining, “I will put him out of his misery. Or perhaps it will be mine.” These passages illustrate the blurring of moral boundaries and reality, reflecting Magda’s psychological disintegration.

The use of first-person narration intensifies the tension, immersing the reader in Magda’s mind while raising questions about the reliability of her account. The farm becomes both a physical and psychological space of confinement.

5. Arrival of the Outsider: The Foreman

A significant turning point occurs with the arrival of the farm’s foreman, a figure representing intrusion and the possibility of connection—or further isolation. Magda projects her desires and fears onto him, blending sexual tension, rivalry, and animosity. She alternates between longing for attention and asserting her dominance, revealing complex power dynamics: “I want him to notice me, yet I want him to obey me. I want to be feared, to be desired.”

This interaction highlights the novel’s exploration of gender, power, and control. Magda’s fantasies and manipulations illustrate how her isolation warps relationships, creating a psychological landscape as harsh as the physical one she inhabits.

6. Magda’s Confession and Psychological Breakdown

Toward the latter part of the novel, Magda’s narrative shifts into a confessional mode, confronting both imagined and real transgressions. She reflects on her desires, resentments, and violent impulses, exposing the full extent of her psychological isolation: “I am the last person on earth who can understand me, for everyone else is already gone or else never existed.”

This confessional tone merges with Coetzee’s existential concerns, exploring the consequences of total isolation, the fluidity of memory, and the unreliability of self-perception. Magda’s inner world becomes increasingly labyrinthine, with fantasy and reality merging into a singular, oppressive experience.

7. The Climactic Resolution

The novel culminates ambiguously, with Magda’s fantasies of violence and domination unresolved. The father’s fate, as well as Magda’s ultimate trajectory, is left uncertain, reinforcing the novel’s meditation on the unknowability of others and the instability of perception: “I will write my own story, and no one will know if it is true or not.”

This unresolved ending emphasizes Coetzee’s focus on psychological realism and existential ambiguity. Magda remains trapped within her isolation, her narrative a testament to human desire for control and understanding in a world indifferent to individual suffering.

Thematic Analysis

1. Isolation and Alienation

Isolation is the central theme of In the Heart of the Country. Magda’s physical separation on the farm mirrors her emotional and psychological detachment. Coetzee portrays the Karoo landscape as both a literal and symbolic space of alienation, where human connection is scarce, and the self becomes a mirror of solitude. Magda’s inner monologues reveal the corrosive effects of prolonged isolation on morality, perception, and desire.

2. Power and Control

The novel explores power dynamics within family, gender, and social hierarchies. Magda’s obsessive focus on her father and her interactions with the foreman highlight struggles over dominance and autonomy. Her fantasies of murder and manipulation are extreme manifestations of a desire to assert control in a life otherwise constrained by circumstance. Coetzee uses these dynamics to question authority and examine the moral consequences of absolute power, even in intimate spaces.

3. Fantasy vs. Reality

Coetzee blurs the boundaries between fantasy and reality, creating a psychological landscape where Magda’s perceptions cannot be trusted. The narrative’s fragmented, confessional style reflects the instability of memory and the human tendency to reconstruct reality according to desire and fear. This thematic tension enhances the novel’s unsettling atmosphere, prompting readers to interrogate the reliability of narrative voice and perception.

4. Gender and Desire

Magda’s position as a solitary woman on the farm underscores themes of gender, sexuality, and power. Her fantasies often intertwine desire with domination, suggesting that isolation and social constraint distort natural human impulses. Coetzee interrogates traditional gender roles through Magda’s complex psychological makeup, exposing how societal pressures and solitude can warp both identity and morality.

5. Existential Reflection

The novel’s sparse prose and reflective monologues convey existential concerns. Magda confronts questions of existence, meaning, and mortality against the indifferent backdrop of the South African landscape. Her obsessive self-examination and moral ambiguity mirror broader existential questions about human freedom, responsibility, and the search for meaning in a barren world.

Stylistic and Literary Features

-

First-Person Narration: The entire novel is filtered through Magda’s consciousness, creating intimacy and immediacy while questioning narrative reliability.

-

Fragmented Structure: The novel’s episodic, non-linear structure mirrors Magda’s psychological fragmentation and emphasizes thematic resonance over plot continuity.

-

Minimalist Prose: Coetzee’s sparse style reflects the starkness of the Karoo and reinforces the intensity of Magda’s inner life.

-

Symbolism of Landscape: The farm and surrounding landscape function as extensions of Magda’s mind, symbolizing both isolation and the harsh realities of existence.

Notable Quotes

-

“I have been alone here since my mother died. Alone with my father.” – Establishing Magda’s isolation.

-

“I walk the land as if to measure my life against it, to see if there is room for me, or if I have already been swallowed.” – Reflections on insignificance and existential struggle.

-

“I will put him out of his misery. Or perhaps it will be mine.” – Illustrating the blurring of fantasy and reality.

-

“I want him to notice me, yet I want him to obey me. I want to be feared, to be desired.” – Exploration of gender, desire, and power.

-

“I am the last person on earth who can understand me, for everyone else is already gone or else never existed.” – Highlighting isolation and psychological alienation.

-

“I will write my own story, and no one will know if it is true or not.” – Emphasizing narrative control and existential ambiguity.

Conclusion

In the Heart of the Country is a psychologically rich, thematically complex novel that interrogates isolation, power, gender, and morality. Through Magda’s monologues, Coetzee creates an intimate yet unsettling portrait of a solitary mind grappling with desire, violence, and existential uncertainty. The novel’s ambiguous ending, sparse prose, and fragmented structure reinforce its themes, leaving readers with profound questions about human nature, perception, and the consequences of solitude.

By combining scene-by-scene breakdown with thematic analysis, this summary captures the novel’s intricate narrative architecture and existential resonance. Coetzee’s exploration of the human psyche in the stark South African landscape continues to challenge readers to confront uncomfortable truths about power, desire, and isolation.