Introduction: A Voice at the Confluence of History, Culture, and Ecology

|

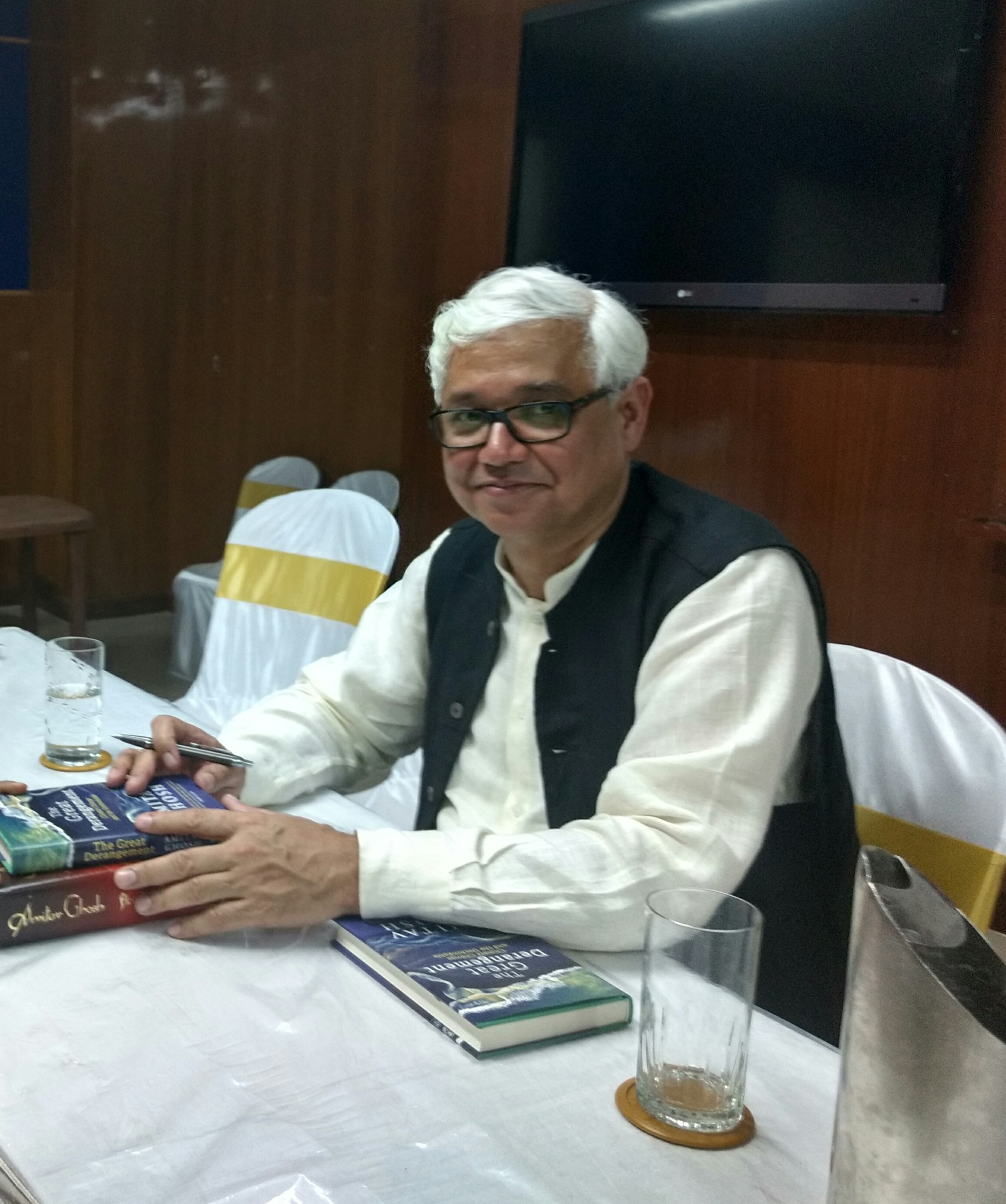

| Amitav Ghosh David Shankbone, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons |

In an age when literature often succumbs to either historical nostalgia or fragmented modernist experimentation, Ghosh achieves a rare balance—retaining the narrative pull of traditional storytelling while pushing the boundaries of form. His ability to weave meticulous archival detail into stories populated by vibrant, symbolic characters ensures that his novels are both intellectually engaging and emotionally immersive.

The following study examines Amitav Ghosh’s literary style and narrative technique, his symbolic characters, his use of irony and satire to comment on contemporary society, his deep engagement with human psychology, his reflections on South Asian social norms, and the emotional transformations of his characters in altered environments. It also considers his literary experiments and innovations, the influences that shaped his craft, and provides critical summaries and analyses of six of his major novels.

Narrative Style and Technique

|

| Amitav Ghosh Shyamal, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons |

In The Shadow Lines, for example, the unnamed narrator reconstructs family memories, political events, and fragmented stories to show that history is as much about perception as about fact.

Ghosh employs non-linear storytelling, allowing readers to see the same events refracted through different cultural, temporal, and emotional lenses.

His narrative voice often blends the intimacy of oral storytelling with the precision of historical scholarship. Archival detail, such as ship logs, colonial records, and botanical descriptions, is meticulously incorporated into the fictional world without becoming dry. In Sea of Poppies, for instance, he not only reconstructs the opium trade but also integrates the Laskari pidgin spoken by sailors, adding authenticity and linguistic richness to the text.

This linguistic hybridity is a key part of his technique—dialects, slang, and non-English terms are retained and contextualized, immersing readers in the polyglot reality of colonial encounters.

Ghosh’s narrators often occupy a liminal position, standing between cultures, geographies, or historical moments. This allows them to question official histories and bring to light marginalized perspectives. His prose moves effortlessly between lyrical description—such as evoking the tidal rhythms of the Sundarbans in The Hungry Tide—and biting irony when exposing hypocrisy, greed, or colonial arrogance.

Symbolic Characters

Ghosh’s characters frequently function on two levels: as fully realized individuals and as symbolic embodiments of larger historical or philosophical forces. In The Glass Palace, Rajkumar, the Burmese-Indian orphan who becomes a teak and oil magnate, represents both the resilience and moral compromises of colonial capitalism. Dolly, his wife, embodies the quieter persistence of cultural memory amid displacement.

In The Hungry Tide, Piyali Roy, the American-educated cetologist of Bengali descent, stands for the modern diasporic intellectual—rooted in science and global networks, yet drawn to ancestral landscapes and their ethical dilemmas. In Sea of Poppies, Deeti’s journey from a marginalized widow in Bihar to a migrant aboard the Ibis ship becomes a microcosm of the vast and often coercive migrations of the colonial era.

These characters are never static allegories; rather, they evolve under the pressures of environment, historical change, and personal relationships. Yet their symbolic dimension allows Ghosh to explore ideas—migration, hybridity, exploitation, resistance—without sacrificing narrative momentum.

Irony, Satire, and Social Commentary

Irony is one of Ghosh’s sharpest tools in critiquing both colonial and contemporary social orders. His satire often exposes the absurdities of imperial bureaucracy, the hypocrisies of nationalist rhetoric, and the moral blindness of economic ambition. In River of Smoke, the opium merchants of Canton justify their trade with lofty talk of free commerce, even as addiction devastates communities in China and India. Ghosh’s irony here is double-edged: it reflects both the blindness of the 19th-century elite and the uncomfortable parallels with modern corporate rationalizations.

Similarly, in The Shadow Lines, the narrator’s family discusses political events with patriotic fervor, yet personal relationships are shaped by the same prejudices and divisions they claim to oppose. This juxtaposition underscores Ghosh’s satirical vision: progress in rhetoric often masks stagnation in practice.

Human Sentiments and Psychological Depth

Ghosh’s fiction excels at portraying the interior landscapes of his characters. He is attuned to the quiet moments of doubt, grief, longing, and joy that define human experience. In The Hungry Tide, Piya’s interactions with Fokir—marked by cultural and linguistic gaps—are infused with an unspoken tenderness that transcends conventional romantic arcs. The emotional depth lies as much in what is left unsaid as in dialogue.

In The Glass Palace, the displacement of the Burmese royal family is rendered not merely as a political event but as a profound personal loss: the shattering of identity, the fading of rituals, the erosion of a way of life. Ghosh’s psychological insight often emerges through the sensory: smells of a lost homeland, textures of familiar objects, the rhythm of remembered songs.

Views on Local Social Norms

Ghosh engages critically with the norms and customs of South Asian societies. His works address the intersections of caste, gender, and religion, often showing how these structures are both resilient and mutable. In Sea of Poppies, caste hierarchies dissolve under the pressures of migration, yet their echoes persist in how characters perceive each other. In The Shadow Lines, communal tensions serve as a reminder that nationalist unity is often fragile and contingent.

He neither romanticizes tradition nor uncritically embraces modernity. Instead, his narratives explore the spaces where social norms are tested—by love that crosses boundaries, by economic necessity, by ecological disaster. This nuanced approach allows him to portray South Asia as a dynamic, contested, and diverse cultural space.

Emotional Transformations in a Changing Environment

Environmental change, whether gradual or catastrophic, is central to many of Ghosh’s plots. The Sundarbans of The Hungry Tide are a place of beauty and danger, where tides erase human boundaries and cyclones alter destinies. In Gun Island, climate change is not a distant abstraction but a lived reality that reshapes migration, labor, and survival.

Characters are often forced to reconfigure their sense of self in response to environmental shifts. Displacement—whether from war, trade, or rising seas—becomes both a physical and emotional journey. Through these arcs, Ghosh shows that identity is not fixed but evolves under the pressures of changing landscapes.

Literary Experiments and Innovations

Ghosh is a literary experimenter. His novels blend genres—historical fiction, travel writing, eco-fiction, and linguistic anthropology. He often constructs narratives from multiple temporal layers, intercutting past and present to show continuity and rupture. The Ibis Trilogy, for instance, is as much a maritime epic as it is a study of imperial economics and cultural contact zones.

His integration of non-English vocabularies without italics or translation glosses reflects a commitment to linguistic authenticity and resists the anglicization of non-Western worlds. This technique immerses readers while challenging them to engage actively with the text.

Life, Influences, and Contemporaries

Amitav Ghosh’s upbringing in India and his formative years in Bangladesh, Sri Lanka, and Egypt exposed him to diverse cultural and linguistic environments. His academic background in social anthropology shaped his interest in the textures of everyday life and the patterns of human migration. Influences range from V. S. Naipaul’s diasporic consciousness to Gabriel García Márquez’s magical realism—though Ghosh’s magic lies more in the uncanny intersections of fact and fiction than in overt fantasy.

Contemporary South Asian writers such as Salman Rushdie and Anita Desai also provided models for blending postcolonial critique with stylistic innovation. Yet Ghosh’s ecological focus and historical depth set him apart, giving his work a distinctive voice in the global literary conversation.

Critical Summaries and Insights on Six Major Novels

|

| Amitav Ghosh David Shankbone, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons |

1. The Shadow Lines (1988)

The Shadow Lines is a landmark in Indian English literature and perhaps Ghosh’s most celebrated early novel. It is not simply a story about a family, but a meditation on how personal memory and national history interlock and sometimes conflict.

The unnamed narrator reconstructs a mosaic of recollections involving Calcutta, London, and Dhaka, showing that the boundaries between past and present, fact and fiction, are not only blurred but often invented.

Tridib, the narrator’s cousin, becomes his guide to seeing beyond maps. In a defining line, Tridib tells him: “What you see is not necessarily what you remember, and what you remember is not necessarily what happened.” This observation, deceptively simple, destabilizes the reader’s trust in linear history. It suggests that memory is an act of imagination, and that the stories we tell ourselves are shaped as much by desire and emotion as by fact.

The 1964 Dhaka riots serve as a pivotal moment, when private grief intersects with public violence. May Price, witnessing the human cost, remarks, “It’s not a question of a place being more or less violent, it’s a question of whether you can look away.” Here, Ghosh critiques the passivity of distant spectators, making the novel a moral as well as political inquiry.

By the end, “shadow lines” emerge as a metaphor for the arbitrary borders of nation-states and the invisible boundaries of class, culture, and ideology. In Ghosh’s hands, these lines are shown to be sustained by shared illusions — they exist because people believe in them.

2. The Glass Palace (2000)

Spanning more than half a century, The Glass Palace situates private lives within the tectonic shifts of empire. The British invasion of Burma in 1885 uproots both the Burmese royal family and ordinary people like Rajkumar Raha, an Indian orphan who claws his way into the teak and oil industries.

The novel’s opening is suffused with a sense of irrevocable change: “There was a sense of a great uprooting; people running, their faces masks of bewilderment.” This visual of sudden displacement foreshadows the broader theme — that history is experienced first as shock and rupture before it becomes a subject for archives.

Rajkumar’s success is inseparable from the moral compromises of colonial capitalism. He acknowledges bluntly: “In this world, you have to take what you can, when you can.” This pragmatism, stripped of ethical qualms, reflects the opportunism that fueled both personal fortunes and imperial expansion.

Dolly, by contrast, becomes a vessel for cultural memory. Separated from her homeland yet unwilling to let it vanish entirely, she says of the lost Burmese palace: “The place is gone, but it lives in us; it has to, or else we are nothing.” Her insistence that heritage survives in the imagination gives the novel a counterpoint to Rajkumar’s materialism.

Through these contrasting characters, Ghosh examines the dual legacies of empire — its capacity to create wealth for some while erasing entire cultural landscapes for others. The result is a layered portrayal of survival, ambition, and memory across generations.

3. The Hungry Tide (2004)

With The Hungry Tide, Ghosh turns from the sweep of global trade to the intimate yet equally vast world of the Sundarbans — a tidal delta where land and water are in constant negotiation. Piyali Roy, a Bengali-American cetologist, comes in search of the rare Irrawaddy dolphin. Her journey brings her into contact with Kanai Dutt, a sophisticated translator, and Fokir, an illiterate fisherman whose knowledge of the tides is instinctive.

Language — or the lack of a shared one — becomes a metaphor for both connection and limitation. When Piya and Fokir first work together, Ghosh writes: “They had no language in common, yet they understood each other better than they could have imagined.” This mutual understanding without words mirrors the way people must often navigate cultural or ecological divides: through observation, empathy, and trust.

The novel also confronts the violent history of human settlement in the Sundarbans, particularly the Morichjhanpi massacre of 1979, when refugees were evicted from protected lands. Kanai’s discovery of his uncle’s diary forces him to question the ethical contradictions of conservation: “Was it the lives of animals that mattered more, or the lives of people?”

The ebb and flow of the tide serve as a structural rhythm for the novel, reminding readers that permanence is illusory. In the Sundarbans, as in life, survival depends on adaptation to forces beyond human control.

4. Sea of Poppies (2008)

The first volume of the Ibis Trilogy, Sea of Poppies, is a sprawling maritime epic set in the years before the First Opium War. It brings together an eclectic cast — Deeti, a widowed poppy farmer; Zachary Reid, a mixed-race American sailor; and Neel Rattan Halder, a disgraced Bengali landlord — aboard the Ibis, bound for Mauritius with a cargo of indentured laborers.

The novel’s opening in Deeti’s poppy fields is lush yet unsettling: “It was the season of opium harvesting, when the flowers bled milky tears.” This image fuses beauty and exploitation, encapsulating the colonial economy’s dependence on the commodification of life itself.

Aboard the Ibis, old hierarchies dissolve even as new ones form. The shipboard “zubben,” a pidgin of English, Hindi, Portuguese, and other languages, becomes a living testament to cultural hybridization. Zachary observes, “On this deck, words had no homeland,” capturing both the fluidity and instability of identities forged in transit.

In Sea of Poppies, the sea is not merely a setting but a liminal zone where the characters’ pasts loosen their grip and uncertain futures beckon. Ghosh makes migration — often forced or coerced — the crucible in which new forms of community emerge.

5. River of Smoke (2011)

The second installment shifts to Canton in 1838, on the brink of the First Opium War. The city teems with traders, artists, and political tensions. At the heart of the novel is Bahram Modi, a Parsi merchant whose fortune rests on opium.

Bahram embodies the moral compromises of global commerce. Confronted with Chinese opposition to the trade, he asserts, “If a man’s right to trade is taken away, he is no better than a slave.” His rhetoric of liberty cloaks a deeper truth — that his wealth depends on addiction and misery. Ghosh thus exposes how the language of “free trade” has long been used to justify exploitation.

Running parallel to Bahram’s arc are the stories of Neel, now a polyglot go-between navigating the cultural complexity of Canton, and Paulette, a botanist seeking rare specimens. These threads allow Ghosh to explore art, science, and commerce as interconnected realms of empire. The novel’s title — River of Smoke — evokes both the physical haze of opium in the air and the moral haze in which imperial powers operate.

Where Sea of Poppies is about departure and displacement, River of Smoke is about arrival and entanglement — the slow realization that once within the web of empire, escape is nearly impossible.

6. Flood of Fire (2015)

In Flood of Fire, the trilogy’s conclusion, Ghosh immerses the reader in the chaos of war. The outbreak of the First Opium War provides the backdrop for a narrative that is both panoramic and deeply personal. Havildar Kesri Singh, a sepoy in the East India Company’s army, offers an insider’s view of military discipline and colonial service.

Kesri’s reflection — “A soldier’s honour is to obey, but a man’s honour is to know why he obeys” — distills the novel’s central moral question: when does loyalty become complicity? His struggle mirrors that of entire societies caught between resisting imperial power and serving it.

Zachary’s journey reaches a dark culmination here. Once an innocent sailor, he succumbs to the temptations of profit and power, becoming a participant in the very trade he once viewed from the margins. His transformation underscores how war accelerates moral erosion.

The “flood” in the title operates on several levels: the literal surge of armies, the tide of imperial ambition sweeping across Asia, and the irreversible currents of globalization unleashed by the conflict. The trilogy ends with characters scattered and altered, their identities shaped by forces beyond their control — a fitting close to Ghosh’s meditation on the human cost of history.

Conclusion: Legacy and Contemporary Relevance

Amitav Ghosh’s work is both a repository of history and a mirror to our own moment. His ability to humanize vast historical processes, to illuminate the ties between ecological change and human destiny, and to craft narratives that are as linguistically rich as they are emotionally resonant, makes his contribution to literature invaluable. His novels remind us that the forces shaping our world—migration, empire, environment—are not abstract concepts but lived realities, etched in the lives of individuals whose stories deserve to be told.