The Quiet Pulse of Fiction in a Noisy Age

: Why Stories Like Diary of a Bad Year Still Matter

The subway hums its tired song as the city slides by in streaks of gray and neon. A man grips a paperback—creased spine, dog-eared edges, the smell of old paper wafting with each turn of the page. Around him, screens glow like restless planets. News tickers scroll. Notifications vibrate. Someone laughs at a video no one else can see. And still the man reads, lips gently shaping silent words, as if listening to a confession meant only for him.

In that small act—almost invisible, almost archaic—fiction shows its relevance.

As the train rattles forward, those worlds weave themselves around the reader’s breathing, asking questions no headline will linger on long enough to ask.

|

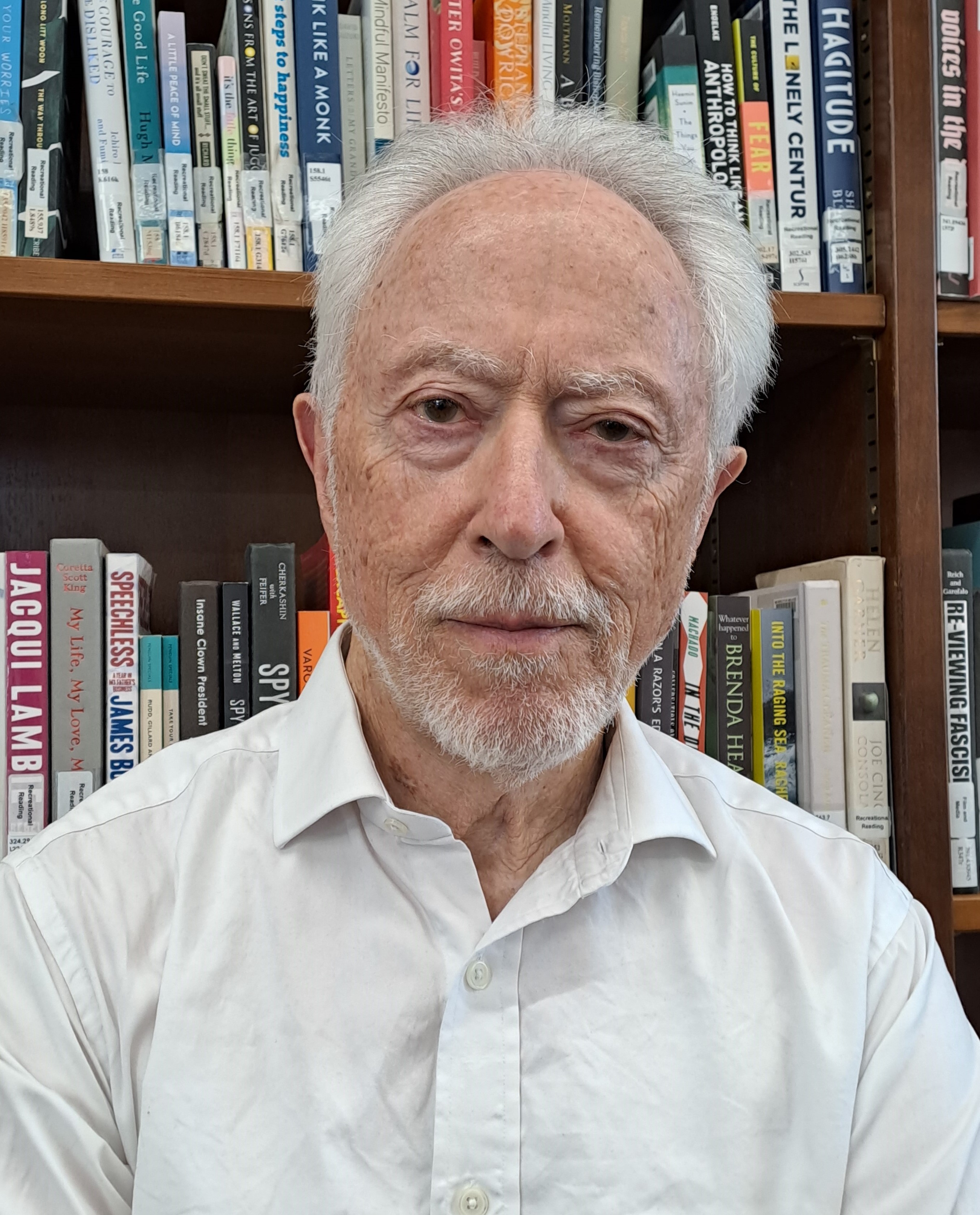

| J.M. Coetzee Laterthanyouthink, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons |

Fiction as a Meeting Place Between Chaos and Clarity

Walk into any modern living room at dusk: a TV murmurs in the corner, two or three devices compete for attention on the coffee table, and half-read articles sit abandoned in browser tabs.

The atmosphere buzzes with information but starves for reflection. In this setting, fiction behaves almost like an insurgent act—one that rearranges the disorder.

Think of Diary of a Bad Year: not a lecture, though it contains essays; not a diary, though the title suggests it; not a love story, though longing tinges its margins. Its very structure—multiple columns unraveling simultaneously—mirrors the layered consciousness of someone living in an age of information saturation. You don’t read it the way you scroll through feeds. You move slowly, aware that each line echoes another, aware that each idea bends the light differently.

In this way, fiction doesn’t compete with the torrential stream of content. It interrupts it—gently, insistently—by reminding readers what careful thinking feels like.

Walking Beside the Author in the Present Moment

Picture a quiet kitchen in the early hours of the morning. A kettle hisses. A notebook sits open on the counter, a pen resting against its spine like a companion waiting for a walk.

Someone reading Diary of a Bad Year raises their eyes from the page and simply breathes. They’ve just encountered a passage about the moral responsibilities of citizens or the uneasy relationship between governments and individuals. Outside the window, garbage trucks groan down the street; the world carries on, indifferent.

But inside the reader’s mind, something shifts. A thought loosens. Another takes root. The present moment—normally so rushed—acquires depth.

This is the quiet magic of fiction that converses with reality rather than fleeing from it. Coetzee’s novel places philosophical reflection beside the mundane rhythms of living: laundry cycles, awkward conversations, the clatter of dishes. It doesn’t preach relevance. It demonstrates it by showing how thoughts and facts mingle with desire, fear, tenderness, and frailty.

In today’s world—where political opinions harden into slogans and public discourse often resembles a battlefield—fiction’s ability to harbor contradiction becomes indispensable. It gives readers a space big enough for nuance, a space where ideas live next to emotions rather than drowning them out.

The Human Face Behind the Argument

Imagine a street café: chairs clatter, spoons flick against porcelain cups, and the smell of roasted beans curls upward into the late afternoon air. Two people sit across from each other. One scrolls through a political thread on their phone, eyebrows tightening. The other pulls a novel from their bag—a story full of arguments, yes, but also full of the trembling uncertainty of its characters.

Fiction, especially works like Diary of a Bad Year, does not strip ideas of their human carriers. Instead, it shows the reader the person holding the belief—the softness in their voice, the hesitation in their posture, the loneliness that shapes their opinions. Ideas become textured. They breathe.

In an age of outrage cycles and polarization, this humanizing effect is not just relevant; it is urgent.

Search engines might rank content by keywords and popularity, but the mind ranks what it remembers by emotional imprint. Stories create those imprints. They lift ideas out of abstraction and place them in the warmth of lived experience.

A Mirror Held Up to the Reader

On a rain-darkened evening, someone closes a novel and sees their reflection faintly in the window. They see themselves—not as a consumer of information, not as a demographic, not as a scroll of data—but as a person capable of wrestling with truths that have no simple answers.

Diary of a Bad Year is full of questions: What does it mean to be a citizen in troubled times? How does one maintain dignity in a society built on spectacle? What responsibility does an artist have to the world outside their desk?

But the novel never hands the reader a manifesto. It hands them a mirror.

And this mirror is strangely warm, because fiction reflects not only what people already know but what they could become. It shows contradictions not as faults but as evidence of aliveness. It urges readers to practice the rare skill of living with complexity.

In the present era—where opinions harden before they ripen—fiction’s mirror is a necessary instrument, one polished by empathy and imagination.

The Slow-Burning Relevance of the Intimate

Consider the bedroom light at midnight: a soft glow against rumpled sheets, a book resting open like a second pillow. Someone traces a sentence with their thumb. The world outside may roar with headlines and crises, but the world inside this room hums softly, intimately.

This intimacy transforms reading into a form of companionship—for those who feel overwhelmed by the noise, for those who sense that something essential is slipping away. Works like Coetzee’s remind readers that literature is not an escape from reality; it is a training ground for perceiving reality more fully.

The novel’s intertwined columns—ideas above, personal narrative below—echo the dual nature of modern life. Public and private. Collective and solitary. Global and personal. These dualities shape every reader’s day, whether they notice them or not: the heart beating beneath the shirt worn to work, the private grief lodged behind a public smile, the internal ethical dilemmas hidden beneath routine decisions.

Fiction makes these hidden layers visible. It whispers that the private self still matters, that the inner conversation is worth attending to, even in a century of constant display.

A Tool for Ethical Imagination

On a park bench beneath the tremble of autumn leaves, someone reads a passage about the moral weight of violence or the decay of political integrity. A child squeals nearby as pigeons scatter at their feet. A jogger passes. Life continues, messy and unscripted.

But the reader’s mind is elsewhere—testing the boundaries of empathy, stretching toward possibilities not yet lived.

Ethical imagination is one of fiction’s oldest gifts, but never has it been more needed. In a world shaped by rapid technological change, surveillance, climate anxiety, and shifting social norms, readers need more than data. They need the ability to forecast human consequences: how decisions affect real people with real vulnerabilities.

Fiction offers this training repeatedly, gently, insistently. It teaches readers to inhabit perspectives not their own. It cultivates patience for ambiguity and attentiveness to suffering. It offers rehearsal space for moral courage.

And novels like Diary of a Bad Year—quiet, unhurried, reflective—teach this without fanfare. They let the reader feel rather than be instructed.

Fiction’s Relevance Lives in Its Readers

The man on the subway closes his book as the train squeals into the station. He slips it into his coat pocket and steps into the evening rush—a river of footsteps, neon reflections pooling on wet pavement.

This is how fiction remains relevant—not as a relic, not as an escape, but as a companion to modern life. A guide. A lantern held low enough to illuminate the next step but not so bright that it blinds the path.

In a century brimming with information yet hungry for meaning, fiction like Diary of a Bad Year does what no algorithm can do: it restores the internal life of the reader. It shows them the world anew, not through the glare of data but through the steady, humane light of story.